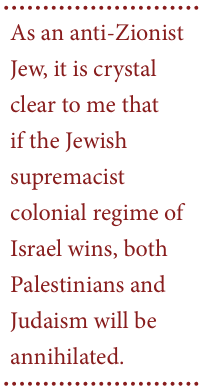

Abstract: “The abolitionist thinking, proliferated particularly by U.S. Black feminist radicals in the wake of the police murder of George Floyd in 2020, exposed police reformism as liberal subterfuge facilitating the expansion of the carceral state. This article utilizes the relationship between police reform and abolition as a prism through which to look at international development aid. If international aid is thought of as a reform effort serving the interests of colonialism, what is the abolitionist approach to international development? This commentary suggests that abolitionist logic grounded in the US-based movement for Black lives can expose international aid reform as a neoliberal tool and simultaneously unmask the potential for a radical vision of development based in a commitment to liberation rather than white/western/northern supremacy. Keywords: abolition, police reform, international development, international aid, colonialism, decolonization, mutual aid, redistribution, reparations.”

This is one of my stranger articles. Writing it made my head hurt! It was informed by my years as an aid accountability activist in Palestine and my experience organizing with the DefundThePolice movement. Read my article in the journal, Decolonial Subversions, main issue, 2023.

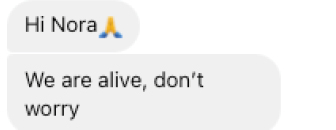

Nurredin Amro has been my friend for more than a decade. For the last eight of those years, he has been fighting to protect his home in Jerusalem from demolition by the Israeli authorities.

Nurredin Amro has been my friend for more than a decade. For the last eight of those years, he has been fighting to protect his home in Jerusalem from demolition by the Israeli authorities.