My tech skills: F

Picking good interviewees: A+

This post was written for the fabulous blog, “Arabic Literature (in English).” You can find the article here. Subscribe to receive a plethora of excellent information about Arabic literature and follow @arablit.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I sat holding my breath in a comfy chair in my friend’s living room. Married to a local (like me), she’s lived in Palestine for a million years under the high ceilings of an old, traditional Ramallah home. It was my favorite night of the week – Wednesday. The Writers’ Circle, a group I instigated under the auspices of the Palestine Writing Workshop, was listening to a stunning young Palestinian read her excerpt. It was about the day when her family, after years of suffering exile as “absentees,” returned to Palestine. A cliché, but true nonetheless: you could have heard a pin drop.

For me, this is the literary scene in Palestine – people writing, people reading, awareness growing, and community deepening.

Looking beyond my narrow experience, it does seem that the literary scene in Palestine, like everything Palestinian, fights against fragmentation by geography and politics. And, like everything Palestinian, the same geography and politics that divide also bind people to the place, to one another, and to literature. The literary scene may be sorely under-developed in relation to its potential, but it is vibrant in its own way.

“There is an intensity here,” one writer told me, “and the literary scene is certainly affected.” The ongoing reality of occupation, colonization, and dispossession gives everything a political significance.

According to Walid Abubaker, prominent novelist, critic and publisher, writers have always been essential to the national movement and the national movement has always been central in Palestinian literature. Since the 1970s, writers have been organized under the umbrella of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Sophie DeWitt, founder and director of the Palestine Writing Workshop, agrees that politics shape the context for Palestinian writing, and often constitute the topic as well. (I myself have wondered if Palestinians write beyond two genres: political non-fiction and political fiction.) I asked Sophie if open wounds hold Palestinian writers back or push them forward, she said, “perhaps both.” Walid is more definite. He says that the golden age of Palestinian literature was in the 1970s and 1980s. Since the Oslo Accords, he laments, refugees and members of the Palestinian diaspora produce better quality than those inside. “If you feel you’ve lost your dream, how can you write?” But a recent profile of four local authors presents a more hopeful view.

The centrality of political themes in Palestinian writing is not only a function of writers’ experiences but also of readers’ needs. I saw it in a dear friend’s eyes and heard it in the tremble of her voice as she talked about the importance of Sahar Khalifeh in her life. I can picture my friend holding Wild Thorns and inhaling; the words oxygenating her cells, steeling her against the harsh reality. I like to imagine that Sahar is nourished in kind by her readers, and especially the Palestinian ones who, in addition to admiration, offer affirmation.

Many Palestinians speak English, certainly among the elite, but not all Palestinians are fluent in Arabic. Therefore, language realities and language politics are an important consideration in local literary activities.

“Even if all the participants in an event speak English, it’s still a political compromise to run the event in English,” Sophie says. “On the other hand, many are making a conscious choice to write in English in order to bear witness.” Some of those books, like Mornings in Jenin, are later translated back into Arabic.

“Writing in other languages, and translation of Arabic texts into other languages, have shown that ours are humanistic experiences that cross national boundaries,” says Renad Qubbaj, Director of Tamer Institute for Community Education. “Brilliant writers like Mahmoud Darwish talk about our local experience in a way that touches everyone. His contribution is greater than merely national. And at the same time, worldwide interest in Palestine has helped propel Palestinian writers onto the world stage.”

Renad notes that Salma al-Jayussi in London, Ibrahim Nasrallah in Jordan, and Ibtisam Barakat in the United States have built international reputations by writing about Palestinian themes. Walid agrees that Palestinian literature in English is important, if only because distribution is so much greater. “We print 1000 copies of a novel in Arabic and it takes 5 years to distribute, even if we give them away for free.”

Does this mean, then, that Palestine is not a nation of readers? Many people are asking this question. Renad says: “We are devastated when people say Arabs don’t read. So we did our own study, which is available in Arabic on Tamer’s website. We found the situation in Palestine is not quite that bad.” She explains: “Literacy has always been considered an aspect of resistance to occupation and a means of resilience. Our literacy rates are among the highest in Arab world, but achievement test scores are lower calling into question the quality of education.”

“We need to develop a value for reading in Palestine,” says Sophie. “Even in university, students read photocopies of books. They don’t know the smell of a public library or how precious it is to build a personal library at home.” That’s why Palestine Writing Workshop has a reading room that is not only a physical space to read, but also a refuge to sit and think and be among books.”

In fact, many NGOs run reading events, organize workshops for writers, host lectures, sponsor contests, etc. But some are critical of the “NGO-ization” of reading and writing. They say it risks prioritizing numbers of participants over substance and quality. “Many people claim to be involved, but,” Walid asks, “do they buy books? Do they read? Do they write? Do they publish?”

Renad points out that there are many diverse sources available, including books, social media, videos, and more. “What we need are promoters that connect the writers with the readers.” In a healthy economy, publishers play this role, but in Palestine, publishing isn’t profitable. “It’s even worse in Gaza,” Renad explains.

“From 2007-2011, the Israelis didn’t allow books into Gaza. They weren’t considered ‘essential.’ Now they do allow books in, but it’s very expensive to transport them. One solution is to reprint books inside Gaza, but the quality can be poor, and this affects interest.”

Moreover, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Education don’t do as much as they should. As a result, most books are produced by NGOs with donations, often from international donors, which is not sustainable.

Mahmoud Muna of the Educational Bookshop in Jerusalem agrees that there is a large and growing community of writers and a smaller but growing community of readers. “One problem is that they aren’t connected,” he explains. The Educational Bookshop tries to address this by organizing events that bring people together around literature. For English readers, there are book launches, author discussions, and film showings. For Arabic readers they have a monthly event organized around authors, not specific books, so that readers get excited about authors and about reading and discussing books. Usually a well-known critic is featured and that draws a crowd, though never as large as for English books.

“Like publishers, authors also don’t make enough money to be able to devote their time to writing,” debut novelist Aref Husseini points out. “That’s why writers need more support.” He believes that reading and writing events are good for involving amateurs in literature, and there are venues for them to publish such as Filistin Ashabab. But there is a dearth of help for talented writers who want to polish their craft so they can advance to the professional ranks. The Palestinian Cultural Forum is a new NGO that seeks to fill that void with the support of local publisher Dar Al-Shorok. Literary actors in Palestine seek to build what Sophie DeWitt calls a “creative economy.”

Even in Jerusalem, where I live, there is a lot going on — despite the fact that West Bank and Gaza participants are prevented entry by military checkpoints. In addition to events at the Educational Bookshop, there are book launches and readings at the American Colony Bookshop and related events at the Press Club and theaters. Authors from around the world come to offer workshops, and books and films are distributed through schools and community libraries.

In May, the Palestine Festival of Literature (PalFest) brings the literary community together in writing workshops, radio journalism training, children’s storytelling, panel lectures, blogging courses, and more that take place in Gaza and the West Bank– enough to keep anyone busy full time just learning about and producing literature. There is, unfortunately, a paucity of activity in the outlying and hard to reach areas.

Regardless of all the challenges, writers will write. They write because they can’t help themselves. Writing is what writers do. Aref says, “I wrote Kafir Sabt because it was a story that had to be written.” Some talented writers may not be able to make the sacrifices that Aref made in order to write his novel. But perhaps over time our collective efforts will enable us to build a literary scene in Palestine that maximizes opportunities for local writers to develop skills, gain recognition, and compete for readership worldwide.

In some places the literary scene might be an enhancement. Here in Palestine it is bread itself — common, coarse, and salty. Writers train and practice and strive to weave words into stories that are uniquely Palestinian, and in doing so, make their experiences universal. For me, it was reading Ghassan Kanafani’s Men in the Sun more than twenty years ago. How could anyone read it and not get involved?

The Palestine Writing Workshop

is pleased to announce as part of

The 5th Annual Palestine Festival of Literature

Upcoming activities, including a children’s literature festival, a series of creative writing workshops, a public literary event, and children’s storytelling.

4 May 2012 (Friday) 9:00 – 16:00

Children’s Activity: A full day Children’s Literature Festival entitled “Cave of Imagination” in the old city of Abwein with Sonia Nimr.

5 May 2012 (Saturday) 10:00-12:00

Workshop: A two hour training on Writing About Culture with writer Rachel Holmes in Birzeit to introduce research and composition skills for writing about culture and the concerns of everyday life.

5 – 11 May 2012

Workshop: A 15 hour (over 5 days) training on creating Stories for the Radio that covers basic journalistic skills with radio journalist Bee Rowlatt, meeting in Birzeit.

5 May 2012 (Saturday) 19:30-21:00

Public Literary Reading: “Representing Lives through Literature” with writers Maya al Hayat, Abed al Rahim al Shaikh, Rachel Holmes, and Bee Rowlatt at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre.

6 May 2012 (Sunday) 14:00 – 16:00

Children’s Activity: Interactive Storytelling in English “The Mornings Smelt Like Chocolate” with Bee Rowlatt at Beit Nimeh, Birzeit.

6 May 2012 (Sunday) 14:30 – 16:30

Workshop: This one day training on Character Development explores how to create characters and bring them to life with writer Rachel Holmes, held in Birzeit.

7 May 2012 (Monday) 14:00 – 17:00

Workshop: This one day training in Birzeit on Draft Editing with writer Rachel Holmes introduces three tools of the writing process to help writers produce well-written, effective texts.

7 May 2012 (Monday) 16:00 – 18:00

Children’s Activity: Interactive Storytelling in Arabic at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center.

8 May 2012 (Tuesday) 16:00 – 18:00

Children’s Activity: Interactive Storytelling in English “The Mornings Smelt Like Chocolate” with Bee Rowlatt at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, Ramallah.

9 May 2012 (Wednesday) 15:30 – 17:30

Workshop: This one day training with writer Rachel Holmes on Publishing Digital Non Fiction is for writers in Gaza and introduces some essential skills for transforming currents events into good, accessible writing. Given via video conferencing.

10 May 2012 (Thursday) 14:30 – 17:30

Workshop: This 3 hour e workshop will be held via video conferencing with journalist Bee Rowlatt for writers in Gaza on Blogging-Get Yourself Out There!

10 May 2012 (Thursday) 17:00 – 18:30

Children’s Activity: Interactive Storytelling in Arabic at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural

Center.

May 11 2012 (Friday) 16:00 – 17:30

Literary Tea with author Rachel Holmes, discussing her book “The Hottentot Venus: the life and death of Saarjtie Baartman: born 1709-buried 2002.” Pick up book in advance to read.

May 12 2012 (Saturday) 11:30 – 13:00

Literary Tea with author Bee Rowlatt, discussing her book “Talking About Jane Austen In Baghdad: The True Story of an Unlikely Friendship.” Pick up book in advance to read.

A big thank you to our partners: Palestine Festival of Literature, British Council, Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, Riwaq, Tamer Institute, and Danish Center for Culture and Development

For more information on any of the above, email us at write@palestineworkshop.org or call +970-(0)597651408

The 2012 PalFest activities are about to begin! I’m hoping to participate more than I did last year. What happened last year? Read this story about my unsuccessful attempt to attend the PalFest 2011 closing event in Silwan.

April 11, 2011: Last night my family was sitting around doing nothing in particular, but I still had to pester and beg and insist that we go out. We live in Jerusalem, a world-class city! Even on the Palestinian side of town, there are things to see. But too often we let the most banal of life’s obligations fill up our time and we get stuck in a rut.

It was the last day of PalFest (the annual Palestinian Literature Festival) and we had already missed most of the contemporary dance festival. My eldest really, really, really didn’t want to go, so she stayed with her friends celebrating the last school day before the Easter break. My middle child, characteristically eager to please me, was happy to join, but she brought a book expecting to bored. My youngest was playing with another 7-year old. I called the girl’s mother, a dear friend, and convinced her to put the girls in her car and drive behind us to PalFest.

The closing event of the 2011 PalFest was being held at the Silwan Solidarity Tent where internationals and locals gather to protest the demolition orders on 80 or so of Silwan’s Palestinian homes. It’s a Palestinian community just adjacent to the Old City, and one that, unfortunately, has religious significance to Jews. It might be a lost cause, but Silwan is going down fighting – hard (get more information here and here).

It only took 10 minutes to get to the corner of the Old City walls where the road curves down and left to Silwan, but that road was roped off. We had forgotten Passover. There are always closures and detours and traffic problems on Jewish holidays, but this one was massive. Cars everywhere with nowhere to go.

We took a right, away from Silwan and drove to the Palestinian bus station to ask a Silwan bus driver (#76 if you ever need to know) what he suggested. He said there are back roads, but it would take more than an hour and we might not get there. We deliberated. My friend had the idea to walk straight through the Old City; Silwan is just beyond the Jewish Quarter. It was 8 pm and the event should have been starting, but the chances were that if we couldn’t get to the venue on time, the performers might also be late. And since the weather was lovely and the kids were awake, we parked near Damascus Gate and walked into the Old City.

I was euphoric. First of all, the Old City is beautiful at night. I don’t remember the last time I was there at night. It was alive and crowded with pushy, noisy vendors and tourists. Taking advantage of the visit, I was quickly able to buy the piece of Palestinian embroidery I wanted to send to my cousin. I was also excited about the line up. DAM, an internationally recognized rap group was playing. Suad Amiry, an internationally recognized author (and friend) was scheduled to MC.

Actually, I saw DAM perform just last week at TEDx in Ramallah (which surreally was held in Bethlehem) and I was hoping they would play their song, “I’m in love with a Jew” about falling in love with a Jew in an elevator (“She was going up, I was going down, down, down”). For some reason, I like that song!

The adults, walking fast to get to the show we were already late for, were followed by the three kids. We took the left fork at the bottom of the Damascus Gate entrance and my friend led us this way and that way until we found ourselves in a sea of black hats. I have never been in the midst (really the midst) of SO many orthodox Jews before and it made me nervous. My friend (who is Palestinian) and I look like foreigners but my husband is clearly Arab. Although no one seemed to notice us or care, I found my stomach tied in nervous knots for the rest of the night.

The checkpoint into the Jewish Quarter was closed and there was already a crowd of angry Jews yelling at the soldiers because they wanted to get in. It didn’t seem smart hang around to watch a fight brew between the Israeli army and religious Jews, so we followed someone’s directions and took two left turns to get to the other entrance into the Jewish Quarter. There, we found ourselves on some stairs in a crowd of hundreds of people standing packed between the narrow alley walls. No one was moving. My husband wasn’t nervous at all (amazing) and asked someone what the delay was (though by talking, most people would know for certain that he’s an Arab). It turned out a “suspicious object” had been found just ahead and that checkpoint was also closed. I pulled my husband away from the crowd, sure that he’d be rounded up. We walked fast into the Arab section where I could breathe again.

We pondered whether we should give up or not, but my friend kept saying, “It’s right there” pointing to the wall. She meant that Silwan was just on the other side of the wall, which was true, but somehow an understatement and an overstatement at the same time. I, too, really wanted to go to that PalFest event. Badly.

Kids in tow, we backtracked to the place where the “suspicious object” had been and found, strangely, the path was open. Completely open. We walked down the stairs and up to the next checkpoint without even slowing down. Jerusalem is such a weird place. Then, despite all the focus on “security,” no one paid any attention to us at the checkpoint because an international guy was carrying a box of what looked like fossilized chips of biblical cooking pots, and the soldiers were so interested, they didn’t pay attention to anyone else. We breezed through that checkpoint and walked straight down to the Wailing Wall. There must have been thousands of people there. It was all lit up. Beautiful in its own right, but so strange to walk through that reality out the Dung Gate to the top of the hill over Silwan, one of Palestine’s hottest hot spots.

Tour busses (Passover, remember?) were lined up to our left but to our right was the entrance to Silwan and nearly empty. We started to walk down the hill toward the solidarity tent, but locals came forward and told us to re-consider. Soldiers had tear-gassed the tent. There was rock throwing. My old activist persona wanted to go anyway, to show support, and to bear witness, but my mother identity won out. It was too dangerous. We turned back.

We had been walking through a maze of human, political, cultural, physical and vehicular obstacles for more than an hour-and-a-half trying to reach a place that was an easy 15-minute drive from our house. We arrived but couldn’t take part. Instead, we went to the Austrian Hospice and had tea and cake.

Here’s a video about PalFest including footage at the end of what we missed:

Now that I have a car, I am often lazy and drive to Ramallah on the days I have business there. It’s best to go early and beat the intense traffic that is inevitable when a population expands and expands over decades but the roads are allowed to decay.

Recently, I drove into Qalandia checkpoint around 7:25 am and my eyes started stinging immediately. Damn tear gas. Not a nice way to start a day. Later I found out that a Palestinian boy had been killed the night before, martyred as they say locally, and the smell of tear gas was remnant from the battle that took his life. Not a battle, really. Palestinian boys with rocks against Israeli boys with guns. More of a set up than a battle.

I shouldn’t drink coffee even on good days. I should definitely not drink coffee on top of tear gas. It was a long, shaky day.

On the way home, there were still tires burning along the side of the main road down to Qalandia. I veered left to take Jeba’a Road (also called death way) and had to swerve around various burning items. That’s not all that unusual, but the smell of fresh tear gas was disconcerting. From a car, you can’t see what’s going on around you. You might unknowingly drive right into danger. I cracked the window and tried to hear.

My friend sat in the front seat next to me and commented casually about the shooting in front of us. I squinted into the dusk and saw long arcs of tear gas shot from the military vehicles up ahead on our left into the community of Ram on our right. I pulled to the side to confer with my friend. “Straight ahead or turn around?” Some cars were driving forward under the tear gas and others were turning around.

“They’re shooting into the air,” she said. “It’s only tear gas. It’s not like we’re going to get shot.” I took that as advice that I should press forward. I, too, wanted to go home, not get stuck on the short stretch of road between two hot spots. I drove fast.

We got to the roundabout near the Israeli settlement and seamlessly resumed our previous conversation about the community’s role in monitoring development projects. The gas was behind us. There was nothing more to say about it.

I got home and washed my clothes separate from our other clothes. I showered and washed my hair three times. My daughter said I smelled good, but my eyes still sting hours later.

Altogether, not an atypical day in Palestine.

“Open the door for me, Im Yaseen,” my mother-in-law says to me. I don’t have a son, but if I did, he would be named Yaseen after my father-in-law. The other daughters-in-law who do not yet have sons are also called “Im Yaseen. It’s like a placeholder for a future identity.

I hold open the screen door so she can get through with a huge metal tray piled with freshly-picked herbs. She balances it expertly on the wall of the front porch in a patch of sun so they can continue to dry.

“I like shaywa’ar more than I like maramiya,” I say reaching deep into the soft pile and inhaling deeply.

“I like maramiya better,” she says. But then, as if not to disappoint me, she adds, “and I like shaywar, too.”

“They aren’t familiar with this herb in Jerusalem. Did you know that?” The things I know better than my mother-in-law are limited to two categories: books (she is illiterate), and the world outside the Galilee (in her 73 years, she has barely traveled).

“Pick out the yellow leaves,” my mother-in-law directs me. And she goes to the backyard to bring another tray of shaywa’ar.

I pick out the yellow leaves and get hypnotized by the sweet, rich smell and the appearance of the delicate, curled leaves bursting from the little twigs. I think about the shaywa’ar I have at home in an old, plastic yogurt container that my mother-in-law gave me last time she dried a batch. I think about those little twigs and how they irritate me floating on the surface of my tea, making it hard to sip without spilling on myself. I decide, out of love for my mother-in-law, to do what she doesn’t have time to do herself—make this batch of shaywa’ar the cleanest batch ever.

I push the big pile of green-gray herbs to the far side of the tray and pull a fist -sized amount toward me. I pick up each twig. When the twigs are dry, the leaves fall right off; when the twigs are still moist with recent life, I have to pull each individual leaf to get it to release. I move the leaves to one side and make a stack of little twigs on the wall.

My mother-in-law sits next to me for a minute. Then she stands up and brings a plastic dish from the kitchen. She puts my little twigs into the plastic dish.

“Did you pick this shaywa’ar wild from the mountain?” I ask.

“No, we cultivated it in our fields.”

“From seeds?”

“From cuttings that we picked in the wild.”

“Does it grow out of control like mint?”

“No,” she answers. “Not like mint.”

And meanwhile, I am focused on cleaning every single twig of its leaves. On impressing my mother-in-law by cleaning her shaywa’ar better than it has ever been cleaned before. On building up my stack of twigs.

A young woman married to my husband’s cousin across the alley comes by for a minute and helps pick through shaywa’ar. Then she leaves. Then my husband’s uncle’s second wife comes by and pulls up a stool and starts picking at the tray. My mother-in-law stands over me although there is a chair for her to sit in.

“Hajji,” my husband’s uncle’s second wife asks my mother-in-law. “Why are you picking out those little twigs?” She gestures towards the plastic plate piled with tiny, naked twigs all lying neatly in the same direction.

“Im Yaseen did that,” she smiles at me politely.

“But they are flavorful,” my husband’s uncle’s second wife says to my mother-in-law, completely ignoring me. “Why do you waste them?”

“Oh!” I snap out of my shaywa’ar-induced trance. “Why didn’t you tell me I was doing it wrong, Hajji?”

“I told you to pick out the yellow leaves,” my mother-in-law says matter-of-factly. And she dumps the stack of neatly piled twigs in the center of the tray of leaves.

I’m not hurt. No one loves me more than my mother-in-law. But I’m a bit embarrassed. After twenty-five years in the family, I can’t do even the simplest of tasks correctly.

I lean back on the heavy plastic chair and let my hands, lightly powdered with nature’s dirt, rest in my lap. I look at the pile of twigs on top of the pile of leaves and identify with them – belonging but separate, giving flavor, but looking out of place.

I know I have to write about what happened in Malha mall, but where can I find the words? Right in front of Aldo shoes, near the H&M where my daughters hold blouses up and ask, “How does this look on me?” and steps away from Lalushka where they buy pointe shoes and leotards – there was a mob riot. Sports fans from the nearby stadium streamed in shouting. They worked themselves into a frenzy chanting “Death to Arabs.” According to the reports, they attacked three Palestinian women with children eating in the food court!

Bad things happen every day here. Every single day someone is kidnapped from his bed in the middle of the night by Israeli soldiers, devastating his wife and children who look on helplessly. Every single day soldiers fire on peaceful protesters, sometimes knocking an eye out, or worse. Every single day soldiers stop young men in the street and frisk them against a wall, shaming them in front of neighbors and making them late for work. And of course there is “nonviolent” violence like revoking people’s residency rights, arbitrarily closing cultural institutions, and the like. It’s sad and scary and infuriating and unacceptable.

But the riot at Malha mall crossed a line. It erased a line! It’s a line that Israel tries to maintain to delude us into thinking that if we behave, everything will be fine, and that only “bad” people are at risk. No! Racism is an attack on all human beings.

PLEASE watch the video of the riot and read the short story and click on the links at this post of Electronic Intifada: http://electronicintifada.net/blogs/ali-abunimah/video-emerges-israeli-mob-shouting-death-arabs-attacked-palestinians-jerusalem#comment-4006. Watch it from beginning to end. Keep watching when it’s upsetting, and when you think it couldn’t possibly go on. Keep watching.

Imagine that this happened at the mall where your kids hang out, or on the bus that your kids take to school, or at a restaurant that you frequent as a family. Imagine the hatred was aimed at you. Imagine that mall security didn’t intervene. Imagine that your local police decided not to arrest anyone. Would you feel safe?

The view from my bedroom window isn’t very pleasing to the eye. That’s because the glass is so dirty. A “good” Palestinian woman spends a significant amount of time attacking the dust and dirt that permeates this place. She throws water on the floor and uses a squeegee to sweep it into drains built into the corner of each room for that purpose. I am a woman, but I am neither “good” nor Palestinian, so, if you visit my house, it is recommended to keep your shoes on.

The window in the living room is cleaner because we have an electric “treese” that we lower when it rains. (I’m sorry but I don’t know how to say “treese” in English and some people here call them “abujur.”) The treese is a slatted shade that comes down on the outside of windows. It is supposed to keep cold and rain out, but in our house rain comes not through the window, but right through the walls. It forms a not-so-small puddle on the floor where my youngest daughter works in her play laboratory.

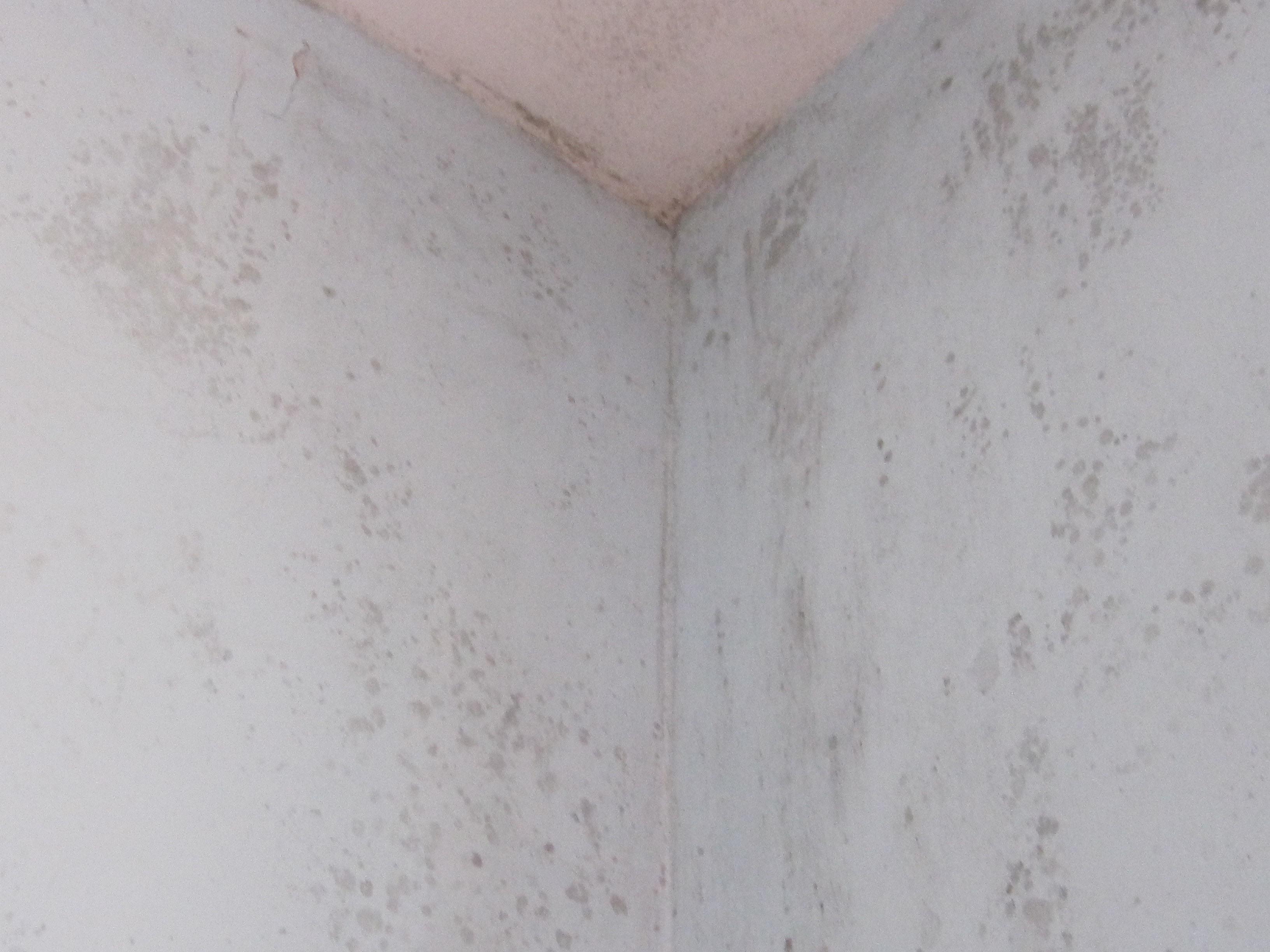

Talking about humidity… these are the patches of mold that seep through the outer walls in the winter. We wipe them off and they come back after a few days.

Why am I telling you this? Well if you’re interested in my life in Palestine, then you need to know about the inconveniences of living in a place where buildings are made poorly (most likely to keep costs down, but the risk of demolition may also be a factor). We also have power outages. And you know you have a problem with water pressure when your 12-year old says, “Mom, can we go to a hotel to have a shower?”

These are problems that the Israeli settlements just ¼ mile from my house do not face. Their infrastructure is updated and maintained, though we both pay the same taxes to the same Jerusalem municipality.

Why do I stay? (My mother keeps asking me that question, too.)

I could move back to my native California or my adopted Massachusetts. But I would miss the storeowner across the street from my apartment who yells at children for dawdling too long as they decide what candy to buy. I would miss Saeeda’s face lighting up as she tells me how women stood up to their husbands in defense of their community projects. I would miss watching my children switch effortlessly from English to Arabic including all the mannerisms and behavior that go with each. I would miss my car, as old and dented and red as I am. And I would miss my mother-in-law. And she would miss me!

So the view from my window in Palestine—dirty, moldy, and inconvenient (not to mention unjust, inhuman and depressing)—is also one of amazing people living important lives. “The view from my window in Palestine” is my point of view. If you’re interested, I’m happy to share it with you.

-Nora

This Week in Palestine, no. 165, January 2012

Available for free at http://www.thisweekinpalestine.com/

I arrived in Busan, Korea, on November 25, awed by the neon lights and by the possibilities. Global leaders were holding the Fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness (HLF4) organised by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and I was an official delegate! It was the most important global meeting on aid policy since the Accra Agenda for Action was endorsed in 2008 and the Paris Declaration in 2005. Both were game changers in their own ways, although Palestine, distinguished as “most aid dependent” by many measures, reaped only negligible benefits. But the HLF4 in Busan was much more promising….

Toolkit (104 pages), January 2012, by Christina Bermann-Harms and Nora Lester Murad

Available for free in English, Spanish and French at www.cso-effectiveness.org/-toolkits,082-.html

The Toolkit is one of the major outputs of the Open Forum process. It is designed for civil society organizations of all types and in all places that wish to put the Istanbul Principles into practice to make their own development work more effective.