UN’s warning that Gaza will not be a “liveable place” by 2020 has been realised. Stephen McCloskey. (15 January 2020). Open Democracy.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/uns-warning-that-gaza-will-not-be-a-liveable-place-by-2020-has-been-realised/

The crisis in the Gaza Strip shames the world as ‘unliveable’ 2020 arrives. Yvonne Ridley. (December 31, 2019). Middle East Monitor. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20191231-the-crisis-in-the-gaza-strip-shames-the-world-as-unliveable-2020-arrives/

By 2020, the UN said Gaza would be unliveable. Did it turn out that way? Donald Macintyre. (December 28, 2019). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/28/gaza-strip-202-unliveable-un-report-did-it-turn-out-that-way

Gaza 2020: Has the Palestinian territory reached the point of no return? Megan O’Toole (December 9, 2019). Middle East Eye. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/what-is-gaza-2020-un-report-uninhabitable-unliveable-blockade

How Gaza was made into an unlivable place. Michael Lynk. (July 24, 2017). Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2017/07/gaza-unlivable-place-170723091946355.html

Gaza in 2020: A Livable Place? A report by the United Nations Country Team in the occupied Palestinian territory. (August 28, 2012).

https://www.unrwa.org/newsroom/press-releases/gaza-2020-liveable-place

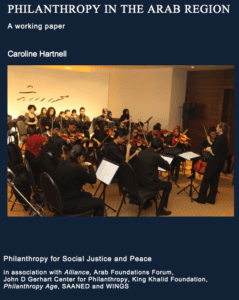

A comprehensive and well-written report, Caroline Hartnell’s just-released

A comprehensive and well-written report, Caroline Hartnell’s just-released