This article about how children’s literature represents Palestine and Palestinians was first published by Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting.

Many children in the United States will never meet a Palestinian in person, and if they do, they may need to overcome the negative images and stereotypes that pervade popular culture: terrorist, religious extremist, misogynist, etc. For this reason, books are a critical if underused opportunity for kids to learn about the people of Palestine.

Palestinians are important because they are human beings, and also because they play a central role in US foreign policy in the Middle East, and are a major focus of US financial and military resources. If US kids are to grow up to be responsible global citizens, they must understand Palestinian experiences and perspectives, among others.

Are US kids getting good insight about Palestinians from books? My ongoing research project examining kids’ books involving Palestine has already yielded some interesting findings: Even the youngest children are subjected to narratives that erase Palestinians.

Erasure through appropriation

Rah! Rah! Mujadara!, for example, is a 12-page board book for ages 1–4 that has an attractive tagline: “Everybody likes hummus, but that’s just one of the great variety of foods found in Israel among its diverse cultures.”

There’s a subtlety in that tagline that may be lost on some. While diversity is acknowledged, it is represented only within the Israeli sphere, without its own history and separate identity.

This is a political position that jibes with Israel’s intentional deployment of the term “Israeli Arabs” to refer to Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, whom Israel wants to incorporate as an Israeli minority, fragmenting them from the larger Palestinian community and from their national identity.

Since Palestinians represent 20% of the citizens of Israel and about 50% of the people who live under Israeli control, readers should expect to see them included. And it is possible that the girl on the top left of the cover is meant to be a Muslim Arab, despite the inauthentic way her headscarf allows her bangs to show.

Newbies to the the Israeli/Palestinian narrative war may also not realize that food is an active battleground. Palestinians consider Israel’s claiming of hummus and falafel, among other foods, to be cultural appropriation.

Palestinians, therefore, are likely to consider both the people and the food appropriated when the same girl is featured behind the text:

Blow, slow.

Taste. Whoa!

Brown fa-LA-fel,

big green mouthful!

Respectful Jewish and Jewish Israeli chefs acknowledge this violence, and counter it by giving credit where credit is due. Since the state of Israel is not even 75 years old, any food with a longer pedigree must have been originated by someone else. But while Kar-Ben Publishing is surely aware of this contention, they either choose to ignore it or intentionally intend to steer readers towards the Israeli narrative—by hiding the Palestinian one.

Cultural appropriation is taken to a new level in Israel ABCs: A Book About the People and Places of Israel (Holly Schroeder, Picture Window Books, 2004).

On page 5, titled “B is for Bedouin,” the text reads: “Bedouins are Arab people who come from Israel’s deserts.” In fact, Bedouins lived on and cultivated land that is now in the State of

Israel for hundreds of years prior to the establishment of the state, and have been systematically discriminated against since. The book’s use of the words “Israel’s deserts” imply that the land belonged to Israel before Arab Bedouins arrived. This is an easy-to-miss example of text that implies that not only does the land belong to Israel, but so do the indigenous Bedouins.

Erasure through deception

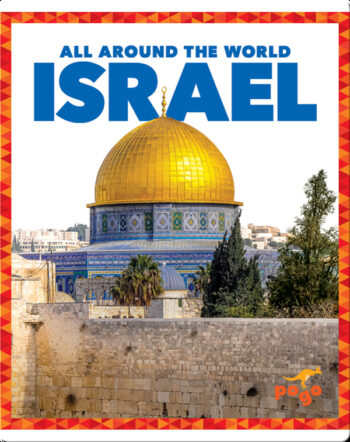

Unfortunately, the erasure of Palestinian reality continues in books for older children. I looked at introductory books about Israel for ages 7–11 years, including All Around the World Israel (Kristine Spanier, Jump!, 2019) and Travel to Israel (Matt Doeden, Lerner Publishing, 2022).

These books share a shocking but easily overlooked flaw: Their covers feature a photo of East Jerusalem alongside the title “Israel.” East Jerusalem is the Palestinian side of the city, previously administered by

Jordan and illegally annexed by Israel following its occupation in the 1967 War. Again, the uninitiated may not realize the significance of linking the state of Israel to East Jerusalem in the minds of readers, and might even think it positive that Israel is making Palestinian areas visible.

However, Israel’s widely condemned annexation of East Jerusalem is illegal under international law. In 1980, Israel declared the “unified” Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, but until Donald Trump moved the US embassy to Jerusalem, not a single country in the world followed suit.

Moreover, Israel has used every possible administrative and military tool available to make East Jerusalem unlivable for Palestinians, in an effort to get them to leave so their land can be repurposed for Jewish use. These cover photos not only fail to acknowledge the reality of life for Palestinian Jerusalemites, they deceptively cover it up.

Putting East Jerusalem on the cover of books about Israel jibes with Israel’s narrative that Jerusalem belongs to Israel, and not to Palestine or the Palestinians, and helps preempt fair and open negotiations

about the final status of Jerusalem as promised in the 1993 Oslo Accords.

Erasure through both-sidesism

Welcome to Israel With Sesame Street (Christy Peterson, Lerner Publishing, 2021) also has a problematic cover, but, consistent with the rest of the book, it is a type of distortion/erasure that can be called “both-sidesism.” The cover is split, with half showing Palestinian East Jerusalem (though a less iconic photo than the Dome of the Rock) and the other half showing an Israeli beach.

Inside, the book continues with this “both sides” approach, starting by teaching children how to say hello in both Hebrew and Arabic (pages 4–5). This “both sides” approach makes a nice visual while hiding Israel’s disrespect for Arabic and Arabic speakers, which is clear in the fact that Arabic had been an official language of Israel until it was officially downgraded in the 2018 Jewish Nation State Law.

Presenting “both sides” is a device used to appear neutral, which conjures a sense of objectivity and truth. It is also a way to stake a claim to antiracism and respect. For example, page 11 says that Jerusalem is “special to people of many religions,” over a photo of Palestinian school girls, some wearing the Muslim hijab.

But presenting Palestinians only as linguistic and religious minorities of Israel, and not as a national group in and of itself, is an Israeli narrative tactic that dehumanizes Palestinians and undermines readers’ ability to understand Israel. While appearing respectful of diversity, the text and photo cleverly omit that Israel is an explicitly, self-declared Jewish state, that enshrines Jewish supremacy over non-Jews (and the corresponding inequality of Palestinians) by saying, in law, that only Jews have the right to self-determination.

Palestine literally erased

Where in the world is Palestine? Nowhere, according to Sesame Street‘s map.

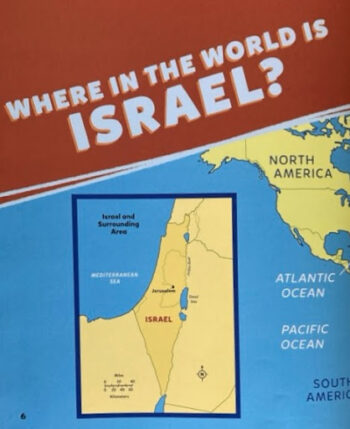

While maps can be controversial when presenting Israel and Palestine, there is one fact that is not controversial: The West Bank and Gaza Strip are not part of Israel. The population of the West Bank and Gaza Strip are not citizens of Israel, and the idea of Israeli annexation of the West Bank has been rejected internationally, including by United Nations officials. Despite this, page 6 of Welcome to Israel With Sesame

Street incorrectly displays a map of Israel (“and Surrounding Area”) including the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the same shade of yellow. The outlines of the occupied Palestinian territory are visible but not labeled. (Notably, the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights is shown as part of Syria.)

While Welcome to Israel With Sesame Street is not the worst of the books I reviewed, it stands out to me because of the Sesame Street branding. Librarians tell me they rely more on reviews than branding when purchasing or recommending books, but as a mom myself, I think parents—and kids—do pay attention to the stamp of credibility that the Sesame Street imprimatur gives to educational materials. Welcome to Israel With Sesame Street illustrates how branding can help to obfuscate rather than illuminate the information we need as global citizens to be constructive problem-solvers.

The Sesame Street brand, and the nonprofit Sesame Workshop that owns it, has previously been criticized for compromises they’ve made in order to address funding shortfalls and stay in business in an increasingly difficult market. Supporters argue that licensing has long been a part of their funding model, and doesn’t necessarily contradict the educational mission that Sesame Workshop has committed to.

Welcome to Israel With Sesame Street, however, is not harmless. It uses subtle messages to contribute to erasure and distortion of Palestinians, which should cause concern among people who care about the educational reputation of the brand. Unfortunately, Sesame Workshop failed to respond to my several inquiries about this book.

Incorporating Palestinian voices

US children will be lucky if they see a book or two mentioning Palestinians in their entire educational careers—so the books they read should be good! There are a few books that offer some age-appropriate information about Palestinians, like ones referenced in Rethinking Schools and listed by the National Council for the Social Studies. These books contribute to an important educational objective—to help students of all ages understand that the world is diverse, that different groups have different experiences, that conflicts and wars hurt people, and that US taxpayers play a role in that. Publishers can do better by incorporating Palestinian voices into their commitments to center diverse voices and by taking a stand to protect and promote Palestinian children’s book writers.