This story was originally published by Arabic Literature in English.

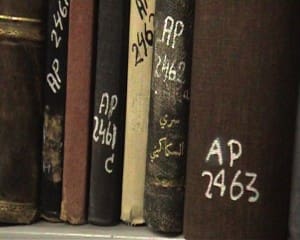

The camera follows two Palestinians with Israeli citizenship from the counter at Israel’s National Library to a table. They carry a small stack books from a collection labeled “AP” for “Absentee Property.” They sit awestruck in front of the books. They touch covers showing respect for the books, their rightful owners, and the Nakba that caused Palestinians to lose their country and heritage.

The camera follows two Palestinians with Israeli citizenship from the counter at Israel’s National Library to a table. They carry a small stack books from a collection labeled “AP” for “Absentee Property.” They sit awestruck in front of the books. They touch covers showing respect for the books, their rightful owners, and the Nakba that caused Palestinians to lose their country and heritage.

One of the Palestinians opens a book and finds “Khalil Sakakini” written by hand in the inside cover. He gasps. The audience watching the film, crammed into the basement floor of Educational Bookshop on Salah Al-Din Street in Jerusalem, is captivated. I crane my neck to see past the tall woman in front of me. The importance of this book, a one-time possession of one of the Arab world’s most important educators and nationalists, jumps off the screen. I feel an unspoken sadness in the room as we grasp the reality: This priceless piece of Palestinian heritage, and so many others, is held by Israel’s National Library.

This scene is one of many gripping scenes in the film, “The Great Book Robbery” shown for the first time in Palestine on January 12, 2013 to an audience of almost 150 people. The documentary by Israeli-Dutch director Benny Brunner unfolds the story of at least 70,000 books looted from Palestinian homes and institutions in 1948. Benny Brunner, a longtime maker of films says of himself: “His work is subversive in nature and has proven to be a thorn in the collective Israeli establishment’s backside.”

It is widely known that when approximately 750,000 Palestinians were expelled or fled from Palestine before and after the establishment of Israel, most Palestinian land and belongings were lost. This film, however, highlights the plight of books. It’s a story that isn’t well-known, and to lovers of books, it is particularly tragic.

According to the film, Gish Amit, a PhD student at the time (2005-9), stumbled by accident upon Israeli documents attesting to the “collection” of Palestinian books in 1948 as he was writing his dissertation about archives. Among papers preserved at the National Library, he found detailed documentation about approximately 30,000 Palestinian books that were taken from private homes and institutions in Jerusalem, by staff of the National Library in coordination with the army. In an article originally published in Haaretz, Amit commented on the fact that documentation of the theft was found in the Library itself. He said, ““It is the paradoxical structure of any archive: the place that preserves the power and organizes it is also the place that exposes the violence and wrongdoing. In this respect, the archive is a place that undermines itself.”

According to the film, Gish Amit, a PhD student at the time (2005-9), stumbled by accident upon Israeli documents attesting to the “collection” of Palestinian books in 1948 as he was writing his dissertation about archives. Among papers preserved at the National Library, he found detailed documentation about approximately 30,000 Palestinian books that were taken from private homes and institutions in Jerusalem, by staff of the National Library in coordination with the army. In an article originally published in Haaretz, Amit commented on the fact that documentation of the theft was found in the Library itself. He said, ““It is the paradoxical structure of any archive: the place that preserves the power and organizes it is also the place that exposes the violence and wrongdoing. In this respect, the archive is a place that undermines itself.”

Only about 6,000 books are still labeled “Absentee Property”—and these, we were told, can be seen by logging into the National Library of Israel and searching by call numbers starting with AP. Brunner speculates that the other 24,000 books that are listed in the documentation are either mixed in with the general collection or have been lost or destroyed. Another 50,000-60,000 books are known to have been looted from other parts of Palestine, mostly textbooks, which Brunner speculated were mostly destroyed or sold. During the discussion that followed the filom, he also made the point that rare manuscripts (estimated by a knowledgeable member of the audience as numbering around 50,000 originating from 56 libraries in and around Jerusalem) are not included in the estimates and are totally unaccounted for. There are rare Palestinian manuscripts in the collection at the National Library, but they are not accessible by the general public. There are also rare Palestinian manuscripts at Hebrew University. “We should remember,” Brunner added, “the film only addresses books that were stolen in 1948. We don’t know the details of what happened in 1967, though we do know there is a pattern of Israeli looting of Palestinian books, photographs and archives, including the PLO archives in Lebanon.”

To prove this point, a member of the audience later told me that a rare copy of Palestine in Pictures from the early 1920s was confiscated by the Israelis when her father crossed Allenby Bridge from Jordan in 1987 after he waited five hours to get it back. He finally asked for and was given a receipt for his book, but as history proves, documentation does not necessarily lead to restitution. The only other copy the owner knows of is in Bodlian Library at Oxford University

The Great Book Robbery, which took five years to make, was broadcast by Aljazeera English and seen in fifty countries, and has also been screened in the three major cinemas in Israel. The director has so far been unable to arrange a showing on Israeli television. Apparently, there is some controversy over whether the original intention was to protect the books or to steal them, but regardless of the original intent, the Israel National Library, in cooperation with the Israeli Custodian of Abandoned Property has kept Palestinian private property for over 64 years and made no effort to return it to its rightful owners. In fact, according to Benny Brunner, until the 1950, each card in the catalogue listed the book with a code that linked it to the place where it came from, thus identifying the original owner. However, those codes were erased in the late 1950s.

Those who watched The Great Book Robbery that night were visibly moved. The film showed the vibrancy of Palestinian literary and cultural life before 1948, how it was stolen (with poignant quotes by a Palestinian prisoner of war who was forced to take part in looting his own village), and the impact on Palestinian identity and well-being today. Many seemed inspired by the movie’s concluding slide which noted that: 1) no effort has been made by Israel to return the stolen books; 2) nor has there been any organized effort by Palestinians to claim them.

Wow what a remarkable story! These books are super important to the existance of the Palestinian People and what can be salvaged of their history. I hope that these books can be shared and that we can learn and know what the culture of pre 1948 was like. This is truely amazing.

Thank you.

I agree. I was quite moved and now I’m doing all I can to encourage other people to show the film and host discussions in their countries. If you are interested, contact the director through the film’s website: http://thegreatbookrobbery.org/

Books are a some part of a much bigger theft..

But is occupation of our homeland our property our way of life, i.e. the people who lived in great tolerance together until the racist invaders came and were given the rule by the British.

The culture that took over our lands and planted itself by terror and arms in our midst cannot survive, it holds a retrograde and dark culture that try hard as it has to corrupt the anyway corruptable it cannot survive.

Yes the books are a loss but such a small one in comparison to the much bigger crime and tragedy.

Thanks for sharing your opinion. I somehow see books as different, not like carpets or musical instruments, or other things that were stolen. Books document history, identity, existence. Their loss is more than symbolic, don’t you think?

I wounder who spoke of carpets.. You can eventually buy other carpets or decide to live without them , but books have something to do with our soul.. It is an added injury to a wound.

We want our lands back and our books ..and musical instruments are sacrosanct for musicians not at all like carpets ..

Perhaps I didn’t express it right, but I agree with you. Totally.