During my recent visit to the United States, I had the honor of being interviewed on a weekly radio program called This Week in Palestine (no relation to the Palestinian print publication This Week in Palestine). “This Week in Palestine” is a 45-minute weekly program which airs every Sunday from 8:00 am to 8:45 am EST on WZBC 90.3 FM Boston College Radio Newton MA. The program is an integral part of Truth and Justice radio, a weekly news program which airs between 6-10 am EST every Sunday.

You can listen to my segment at http://archive.org/details/ThisWeekInPalestineInterviewWithNoraLesterMurad. I talked a bit about why I moved to Palestine, the founding of Dalia Association, and problems with the international aid system.

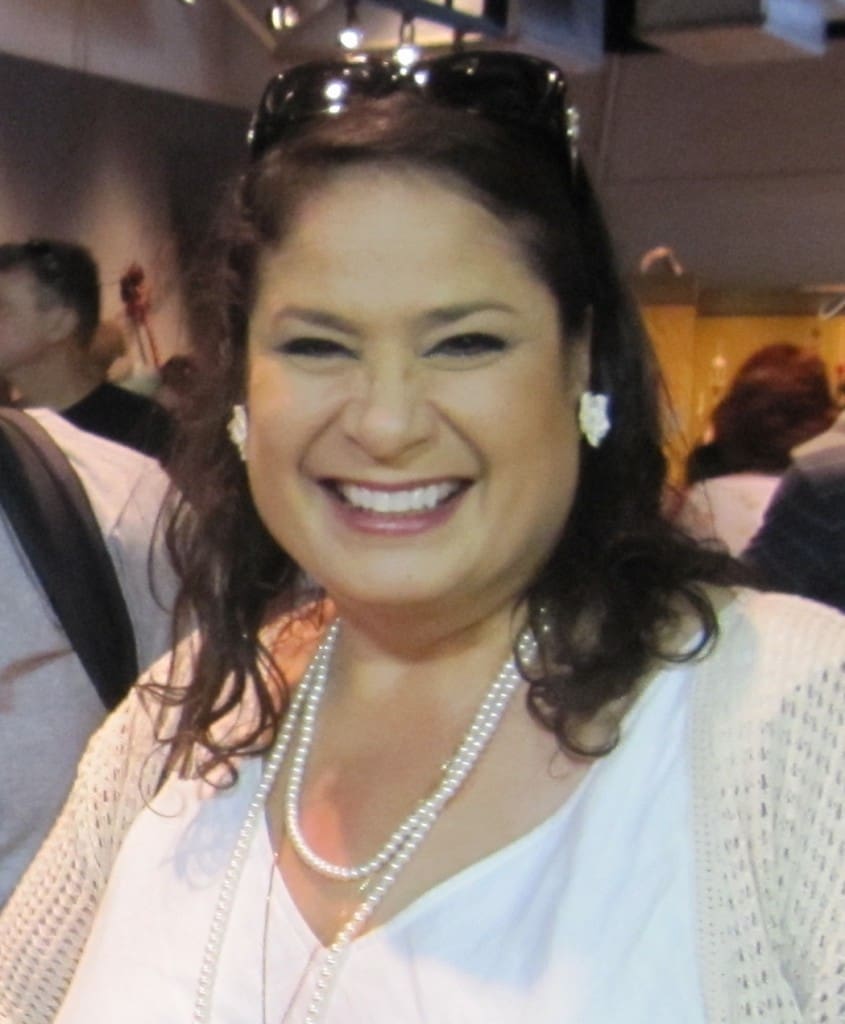

“This Week in Palestine” (TWIP) provides news, opinions and interviews from a Palestinian perspective. The program is a direct outgrowth of participation in the Boston Social Forum in 2004 at UMASS Boston. The program has been on the air for over eight years with local Boston activist Sherif Fam as the host until his untimely death in 2010. The program continues in his loving memory with a team of four co-hosts: Salma Abu Ayash, John Roberts, Chadi Salamoun and Despina Moutsouris. On May 15, 2011 the Community Church of Boston honored TWIP and Truth and Justice Radio with their annual Sacco and Vanzetti Award for promoting truth with justice in the local community. TWIP proudly supports Palestinian self determination, refugee rights, and the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement. The archive of past radio shows can be found on the following website: www.tinyurl.com/twiplist2. The radio station website is www.wzbc.org