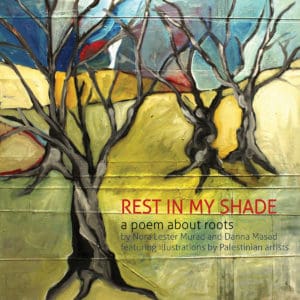

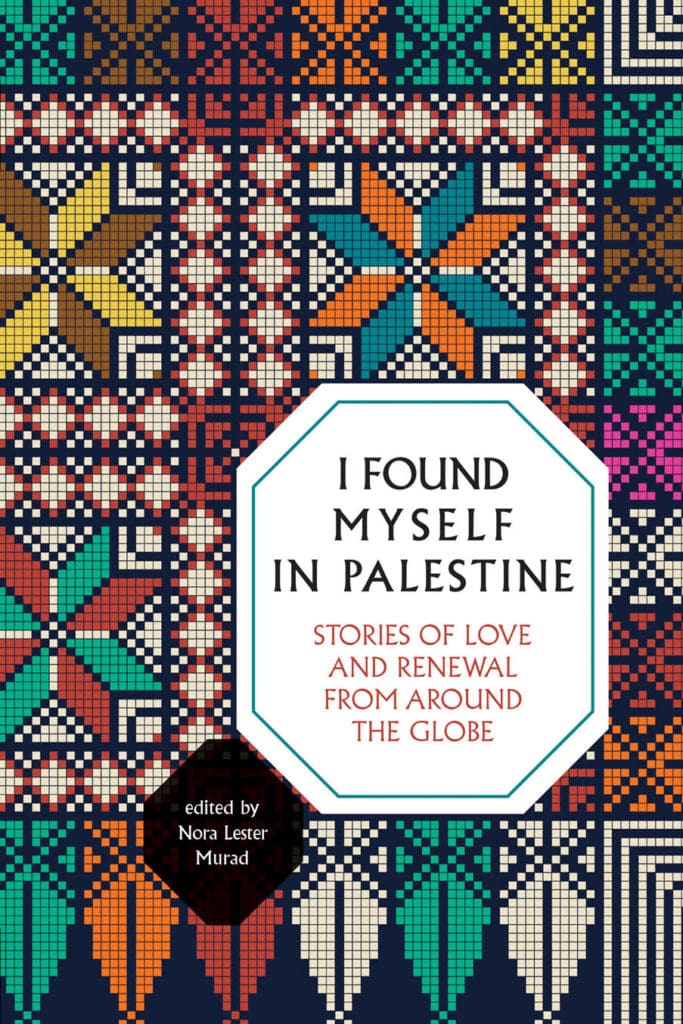

Copies of my second book, I Found Myself in Palestine, arrived from the publisher in the middle of March. The very considerate delivery guy put down the books and moved away. “I’ll sign your delivery receipt,” he said, “so you don’t need to touch my pen and clipboard.”

There is nothing normal about launching a book in the midst of a pandemic.

The cover was beautiful and I liked holding the compact little book in my hands, but it didn’t feel like an accomplishment. It didn’t feel like the culmination of literally years of work by me and the 23 writers featured in the anthology. Honestly, it seemed trivial.

Hundreds of thousands more people have died since then, and the stress of uncertainty in the United States and around the world has grown. But I’m ready to share the book with the world anyway. Some people are reading more these days, and friends tell me that the personal approach of the book may bring calm and inspiration to some people. I hope so.

There is nothing normal about launching a book in the midst of a pandemic, but I hope that I Found Myself in Palestine will remind people that Palestinians, like many others, have experienced uncertainty and death for decades and they have kept their humanity. I hope we can all do the same.