Enjoy 7-minutes of laughter, and please comment if you like this video as much as we do!

Enjoy 7-minutes of laughter, and please comment if you like this video as much as we do!

This story was originally published by Arabic Literature in English.

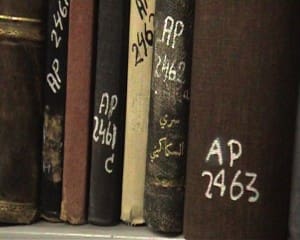

The camera follows two Palestinians with Israeli citizenship from the counter at Israel’s National Library to a table. They carry a small stack books from a collection labeled “AP” for “Absentee Property.” They sit awestruck in front of the books. They touch covers showing respect for the books, their rightful owners, and the Nakba that caused Palestinians to lose their country and heritage.

The camera follows two Palestinians with Israeli citizenship from the counter at Israel’s National Library to a table. They carry a small stack books from a collection labeled “AP” for “Absentee Property.” They sit awestruck in front of the books. They touch covers showing respect for the books, their rightful owners, and the Nakba that caused Palestinians to lose their country and heritage.

One of the Palestinians opens a book and finds “Khalil Sakakini” written by hand in the inside cover. He gasps. The audience watching the film, crammed into the basement floor of Educational Bookshop on Salah Al-Din Street in Jerusalem, is captivated. I crane my neck to see past the tall woman in front of me. The importance of this book, a one-time possession of one of the Arab world’s most important educators and nationalists, jumps off the screen. I feel an unspoken sadness in the room as we grasp the reality: This priceless piece of Palestinian heritage, and so many others, is held by Israel’s National Library.

This scene is one of many gripping scenes in the film, “The Great Book Robbery” shown for the first time in Palestine on January 12, 2013 to an audience of almost 150 people. The documentary by Israeli-Dutch director Benny Brunner unfolds the story of at least 70,000 books looted from Palestinian homes and institutions in 1948. Benny Brunner, a longtime maker of films says of himself: “His work is subversive in nature and has proven to be a thorn in the collective Israeli establishment’s backside.”

It is widely known that when approximately 750,000 Palestinians were expelled or fled from Palestine before and after the establishment of Israel, most Palestinian land and belongings were lost. This film, however, highlights the plight of books. It’s a story that isn’t well-known, and to lovers of books, it is particularly tragic.

According to the film, Gish Amit, a PhD student at the time (2005-9), stumbled by accident upon Israeli documents attesting to the “collection” of Palestinian books in 1948 as he was writing his dissertation about archives. Among papers preserved at the National Library, he found detailed documentation about approximately 30,000 Palestinian books that were taken from private homes and institutions in Jerusalem, by staff of the National Library in coordination with the army. In an article originally published in Haaretz, Amit commented on the fact that documentation of the theft was found in the Library itself. He said, ““It is the paradoxical structure of any archive: the place that preserves the power and organizes it is also the place that exposes the violence and wrongdoing. In this respect, the archive is a place that undermines itself.”

According to the film, Gish Amit, a PhD student at the time (2005-9), stumbled by accident upon Israeli documents attesting to the “collection” of Palestinian books in 1948 as he was writing his dissertation about archives. Among papers preserved at the National Library, he found detailed documentation about approximately 30,000 Palestinian books that were taken from private homes and institutions in Jerusalem, by staff of the National Library in coordination with the army. In an article originally published in Haaretz, Amit commented on the fact that documentation of the theft was found in the Library itself. He said, ““It is the paradoxical structure of any archive: the place that preserves the power and organizes it is also the place that exposes the violence and wrongdoing. In this respect, the archive is a place that undermines itself.”

Only about 6,000 books are still labeled “Absentee Property”—and these, we were told, can be seen by logging into the National Library of Israel and searching by call numbers starting with AP. Brunner speculates that the other 24,000 books that are listed in the documentation are either mixed in with the general collection or have been lost or destroyed. Another 50,000-60,000 books are known to have been looted from other parts of Palestine, mostly textbooks, which Brunner speculated were mostly destroyed or sold. During the discussion that followed the filom, he also made the point that rare manuscripts (estimated by a knowledgeable member of the audience as numbering around 50,000 originating from 56 libraries in and around Jerusalem) are not included in the estimates and are totally unaccounted for. There are rare Palestinian manuscripts in the collection at the National Library, but they are not accessible by the general public. There are also rare Palestinian manuscripts at Hebrew University. “We should remember,” Brunner added, “the film only addresses books that were stolen in 1948. We don’t know the details of what happened in 1967, though we do know there is a pattern of Israeli looting of Palestinian books, photographs and archives, including the PLO archives in Lebanon.”

To prove this point, a member of the audience later told me that a rare copy of Palestine in Pictures from the early 1920s was confiscated by the Israelis when her father crossed Allenby Bridge from Jordan in 1987 after he waited five hours to get it back. He finally asked for and was given a receipt for his book, but as history proves, documentation does not necessarily lead to restitution. The only other copy the owner knows of is in Bodlian Library at Oxford University

The Great Book Robbery, which took five years to make, was broadcast by Aljazeera English and seen in fifty countries, and has also been screened in the three major cinemas in Israel. The director has so far been unable to arrange a showing on Israeli television. Apparently, there is some controversy over whether the original intention was to protect the books or to steal them, but regardless of the original intent, the Israel National Library, in cooperation with the Israeli Custodian of Abandoned Property has kept Palestinian private property for over 64 years and made no effort to return it to its rightful owners. In fact, according to Benny Brunner, until the 1950, each card in the catalogue listed the book with a code that linked it to the place where it came from, thus identifying the original owner. However, those codes were erased in the late 1950s.

Those who watched The Great Book Robbery that night were visibly moved. The film showed the vibrancy of Palestinian literary and cultural life before 1948, how it was stolen (with poignant quotes by a Palestinian prisoner of war who was forced to take part in looting his own village), and the impact on Palestinian identity and well-being today. Many seemed inspired by the movie’s concluding slide which noted that: 1) no effort has been made by Israel to return the stolen books; 2) nor has there been any organized effort by Palestinians to claim them.

Got ya all excited, didn’t I? You thought I had published my picture book, “Because it is Also Your Story” (co-authored with Danna Massad) or my upper middle grade novel, “Amina and the Green Olives.” Actually, neither is published yet, in fact, both are are still seeking representation. And my women’s literary fiction novel, “One Year in Beit Hanina” is still several months away from being a completed first draft.

So why am I announcing my first published book? Because when I was in Pasadena, California this summer, helping my mother move out of her home of 41 years, I found (drum roll) “The Three Fishes.” “The Three Fishes” was my first published book. (Scroll to the end of this post to see it!)

The publisher? Mrs. Paula Rao, a creative, energetic, loving teacher that I had the pleasure of studying with in the first, second and third grades at San Rafael Elementary. She published several of my books, all in hard cover, all with fancy title lettering.

Don’t laugh at my excitement. When you’re seven years old and you don’t know how to write a story (but you also don’t know that you don’t know how to write a story) and a teacher like Paula Rao publishes your book, it matters. You turn a corner. You can imagine yourself as a writer. You can imagine yourself doing anything that you can imagine.

Amidst piles of decades-old memorabilia, I also found a book I wrote that was illustrated by my best friend from those years, Desiree Larsuel (now Rollins). I found another book that I wrote which listed her as editor! I showed the books to Des one night when I took a break from sorting and packing. She laughed and laughed. She remembered those books as clearly as I did. They mattered to her too.

Before the end of the night, Desiree and I (seen in the photo on the left, taken around 1971) were talking about writing a movie, a kind of memoir of our experiences during the early years of integration in Pasadena. You see, my first grade year was the first year of busing — I had attended a segregated kindergarten class in the very same school the year before.

We have many stories yet to tell. Thanks, Mrs. Rao, for helping me to find my voice. I’m using it to give people insight into life in Palestine.

This post was written for the fabulous blog, “Arabic Literature (in English).” You can find the article here. Subscribe to receive a plethora of excellent information about Arabic literature and follow @arablit.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I sat holding my breath in a comfy chair in my friend’s living room. Married to a local (like me), she’s lived in Palestine for a million years under the high ceilings of an old, traditional Ramallah home. It was my favorite night of the week – Wednesday. The Writers’ Circle, a group I instigated under the auspices of the Palestine Writing Workshop, was listening to a stunning young Palestinian read her excerpt. It was about the day when her family, after years of suffering exile as “absentees,” returned to Palestine. A cliché, but true nonetheless: you could have heard a pin drop.

For me, this is the literary scene in Palestine – people writing, people reading, awareness growing, and community deepening.

Looking beyond my narrow experience, it does seem that the literary scene in Palestine, like everything Palestinian, fights against fragmentation by geography and politics. And, like everything Palestinian, the same geography and politics that divide also bind people to the place, to one another, and to literature. The literary scene may be sorely under-developed in relation to its potential, but it is vibrant in its own way.

“There is an intensity here,” one writer told me, “and the literary scene is certainly affected.” The ongoing reality of occupation, colonization, and dispossession gives everything a political significance.

According to Walid Abubaker, prominent novelist, critic and publisher, writers have always been essential to the national movement and the national movement has always been central in Palestinian literature. Since the 1970s, writers have been organized under the umbrella of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Sophie DeWitt, founder and director of the Palestine Writing Workshop, agrees that politics shape the context for Palestinian writing, and often constitute the topic as well. (I myself have wondered if Palestinians write beyond two genres: political non-fiction and political fiction.) I asked Sophie if open wounds hold Palestinian writers back or push them forward, she said, “perhaps both.” Walid is more definite. He says that the golden age of Palestinian literature was in the 1970s and 1980s. Since the Oslo Accords, he laments, refugees and members of the Palestinian diaspora produce better quality than those inside. “If you feel you’ve lost your dream, how can you write?” But a recent profile of four local authors presents a more hopeful view.

The centrality of political themes in Palestinian writing is not only a function of writers’ experiences but also of readers’ needs. I saw it in a dear friend’s eyes and heard it in the tremble of her voice as she talked about the importance of Sahar Khalifeh in her life. I can picture my friend holding Wild Thorns and inhaling; the words oxygenating her cells, steeling her against the harsh reality. I like to imagine that Sahar is nourished in kind by her readers, and especially the Palestinian ones who, in addition to admiration, offer affirmation.

Many Palestinians speak English, certainly among the elite, but not all Palestinians are fluent in Arabic. Therefore, language realities and language politics are an important consideration in local literary activities.

“Even if all the participants in an event speak English, it’s still a political compromise to run the event in English,” Sophie says. “On the other hand, many are making a conscious choice to write in English in order to bear witness.” Some of those books, like Mornings in Jenin, are later translated back into Arabic.

“Writing in other languages, and translation of Arabic texts into other languages, have shown that ours are humanistic experiences that cross national boundaries,” says Renad Qubbaj, Director of Tamer Institute for Community Education. “Brilliant writers like Mahmoud Darwish talk about our local experience in a way that touches everyone. His contribution is greater than merely national. And at the same time, worldwide interest in Palestine has helped propel Palestinian writers onto the world stage.”

Renad notes that Salma al-Jayussi in London, Ibrahim Nasrallah in Jordan, and Ibtisam Barakat in the United States have built international reputations by writing about Palestinian themes. Walid agrees that Palestinian literature in English is important, if only because distribution is so much greater. “We print 1000 copies of a novel in Arabic and it takes 5 years to distribute, even if we give them away for free.”

Does this mean, then, that Palestine is not a nation of readers? Many people are asking this question. Renad says: “We are devastated when people say Arabs don’t read. So we did our own study, which is available in Arabic on Tamer’s website. We found the situation in Palestine is not quite that bad.” She explains: “Literacy has always been considered an aspect of resistance to occupation and a means of resilience. Our literacy rates are among the highest in Arab world, but achievement test scores are lower calling into question the quality of education.”

“We need to develop a value for reading in Palestine,” says Sophie. “Even in university, students read photocopies of books. They don’t know the smell of a public library or how precious it is to build a personal library at home.” That’s why Palestine Writing Workshop has a reading room that is not only a physical space to read, but also a refuge to sit and think and be among books.”

In fact, many NGOs run reading events, organize workshops for writers, host lectures, sponsor contests, etc. But some are critical of the “NGO-ization” of reading and writing. They say it risks prioritizing numbers of participants over substance and quality. “Many people claim to be involved, but,” Walid asks, “do they buy books? Do they read? Do they write? Do they publish?”

Renad points out that there are many diverse sources available, including books, social media, videos, and more. “What we need are promoters that connect the writers with the readers.” In a healthy economy, publishers play this role, but in Palestine, publishing isn’t profitable. “It’s even worse in Gaza,” Renad explains.

“From 2007-2011, the Israelis didn’t allow books into Gaza. They weren’t considered ‘essential.’ Now they do allow books in, but it’s very expensive to transport them. One solution is to reprint books inside Gaza, but the quality can be poor, and this affects interest.”

Moreover, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Education don’t do as much as they should. As a result, most books are produced by NGOs with donations, often from international donors, which is not sustainable.

Mahmoud Muna of the Educational Bookshop in Jerusalem agrees that there is a large and growing community of writers and a smaller but growing community of readers. “One problem is that they aren’t connected,” he explains. The Educational Bookshop tries to address this by organizing events that bring people together around literature. For English readers, there are book launches, author discussions, and film showings. For Arabic readers they have a monthly event organized around authors, not specific books, so that readers get excited about authors and about reading and discussing books. Usually a well-known critic is featured and that draws a crowd, though never as large as for English books.

“Like publishers, authors also don’t make enough money to be able to devote their time to writing,” debut novelist Aref Husseini points out. “That’s why writers need more support.” He believes that reading and writing events are good for involving amateurs in literature, and there are venues for them to publish such as Filistin Ashabab. But there is a dearth of help for talented writers who want to polish their craft so they can advance to the professional ranks. The Palestinian Cultural Forum is a new NGO that seeks to fill that void with the support of local publisher Dar Al-Shorok. Literary actors in Palestine seek to build what Sophie DeWitt calls a “creative economy.”

Even in Jerusalem, where I live, there is a lot going on — despite the fact that West Bank and Gaza participants are prevented entry by military checkpoints. In addition to events at the Educational Bookshop, there are book launches and readings at the American Colony Bookshop and related events at the Press Club and theaters. Authors from around the world come to offer workshops, and books and films are distributed through schools and community libraries.

In May, the Palestine Festival of Literature (PalFest) brings the literary community together in writing workshops, radio journalism training, children’s storytelling, panel lectures, blogging courses, and more that take place in Gaza and the West Bank– enough to keep anyone busy full time just learning about and producing literature. There is, unfortunately, a paucity of activity in the outlying and hard to reach areas.

Regardless of all the challenges, writers will write. They write because they can’t help themselves. Writing is what writers do. Aref says, “I wrote Kafir Sabt because it was a story that had to be written.” Some talented writers may not be able to make the sacrifices that Aref made in order to write his novel. But perhaps over time our collective efforts will enable us to build a literary scene in Palestine that maximizes opportunities for local writers to develop skills, gain recognition, and compete for readership worldwide.

In some places the literary scene might be an enhancement. Here in Palestine it is bread itself — common, coarse, and salty. Writers train and practice and strive to weave words into stories that are uniquely Palestinian, and in doing so, make their experiences universal. For me, it was reading Ghassan Kanafani’s Men in the Sun more than twenty years ago. How could anyone read it and not get involved?

The 2012 PalFest activities are about to begin! I’m hoping to participate more than I did last year. What happened last year? Read this story about my unsuccessful attempt to attend the PalFest 2011 closing event in Silwan.

April 11, 2011: Last night my family was sitting around doing nothing in particular, but I still had to pester and beg and insist that we go out. We live in Jerusalem, a world-class city! Even on the Palestinian side of town, there are things to see. But too often we let the most banal of life’s obligations fill up our time and we get stuck in a rut.

It was the last day of PalFest (the annual Palestinian Literature Festival) and we had already missed most of the contemporary dance festival. My eldest really, really, really didn’t want to go, so she stayed with her friends celebrating the last school day before the Easter break. My middle child, characteristically eager to please me, was happy to join, but she brought a book expecting to bored. My youngest was playing with another 7-year old. I called the girl’s mother, a dear friend, and convinced her to put the girls in her car and drive behind us to PalFest.

The closing event of the 2011 PalFest was being held at the Silwan Solidarity Tent where internationals and locals gather to protest the demolition orders on 80 or so of Silwan’s Palestinian homes. It’s a Palestinian community just adjacent to the Old City, and one that, unfortunately, has religious significance to Jews. It might be a lost cause, but Silwan is going down fighting – hard (get more information here and here).

It only took 10 minutes to get to the corner of the Old City walls where the road curves down and left to Silwan, but that road was roped off. We had forgotten Passover. There are always closures and detours and traffic problems on Jewish holidays, but this one was massive. Cars everywhere with nowhere to go.

We took a right, away from Silwan and drove to the Palestinian bus station to ask a Silwan bus driver (#76 if you ever need to know) what he suggested. He said there are back roads, but it would take more than an hour and we might not get there. We deliberated. My friend had the idea to walk straight through the Old City; Silwan is just beyond the Jewish Quarter. It was 8 pm and the event should have been starting, but the chances were that if we couldn’t get to the venue on time, the performers might also be late. And since the weather was lovely and the kids were awake, we parked near Damascus Gate and walked into the Old City.

I was euphoric. First of all, the Old City is beautiful at night. I don’t remember the last time I was there at night. It was alive and crowded with pushy, noisy vendors and tourists. Taking advantage of the visit, I was quickly able to buy the piece of Palestinian embroidery I wanted to send to my cousin. I was also excited about the line up. DAM, an internationally recognized rap group was playing. Suad Amiry, an internationally recognized author (and friend) was scheduled to MC.

Actually, I saw DAM perform just last week at TEDx in Ramallah (which surreally was held in Bethlehem) and I was hoping they would play their song, “I’m in love with a Jew” about falling in love with a Jew in an elevator (“She was going up, I was going down, down, down”). For some reason, I like that song!

The adults, walking fast to get to the show we were already late for, were followed by the three kids. We took the left fork at the bottom of the Damascus Gate entrance and my friend led us this way and that way until we found ourselves in a sea of black hats. I have never been in the midst (really the midst) of SO many orthodox Jews before and it made me nervous. My friend (who is Palestinian) and I look like foreigners but my husband is clearly Arab. Although no one seemed to notice us or care, I found my stomach tied in nervous knots for the rest of the night.

The checkpoint into the Jewish Quarter was closed and there was already a crowd of angry Jews yelling at the soldiers because they wanted to get in. It didn’t seem smart hang around to watch a fight brew between the Israeli army and religious Jews, so we followed someone’s directions and took two left turns to get to the other entrance into the Jewish Quarter. There, we found ourselves on some stairs in a crowd of hundreds of people standing packed between the narrow alley walls. No one was moving. My husband wasn’t nervous at all (amazing) and asked someone what the delay was (though by talking, most people would know for certain that he’s an Arab). It turned out a “suspicious object” had been found just ahead and that checkpoint was also closed. I pulled my husband away from the crowd, sure that he’d be rounded up. We walked fast into the Arab section where I could breathe again.

We pondered whether we should give up or not, but my friend kept saying, “It’s right there” pointing to the wall. She meant that Silwan was just on the other side of the wall, which was true, but somehow an understatement and an overstatement at the same time. I, too, really wanted to go to that PalFest event. Badly.

Kids in tow, we backtracked to the place where the “suspicious object” had been and found, strangely, the path was open. Completely open. We walked down the stairs and up to the next checkpoint without even slowing down. Jerusalem is such a weird place. Then, despite all the focus on “security,” no one paid any attention to us at the checkpoint because an international guy was carrying a box of what looked like fossilized chips of biblical cooking pots, and the soldiers were so interested, they didn’t pay attention to anyone else. We breezed through that checkpoint and walked straight down to the Wailing Wall. There must have been thousands of people there. It was all lit up. Beautiful in its own right, but so strange to walk through that reality out the Dung Gate to the top of the hill over Silwan, one of Palestine’s hottest hot spots.

Tour busses (Passover, remember?) were lined up to our left but to our right was the entrance to Silwan and nearly empty. We started to walk down the hill toward the solidarity tent, but locals came forward and told us to re-consider. Soldiers had tear-gassed the tent. There was rock throwing. My old activist persona wanted to go anyway, to show support, and to bear witness, but my mother identity won out. It was too dangerous. We turned back.

We had been walking through a maze of human, political, cultural, physical and vehicular obstacles for more than an hour-and-a-half trying to reach a place that was an easy 15-minute drive from our house. We arrived but couldn’t take part. Instead, we went to the Austrian Hospice and had tea and cake.

Here’s a video about PalFest including footage at the end of what we missed: