This review originally appeared in Al-Akhbar.

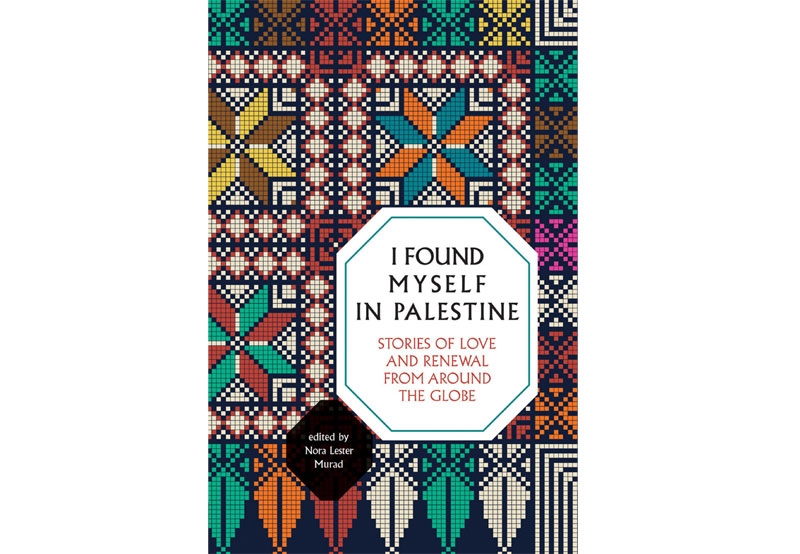

نورا لستر مراد محرّرة كتاب «وإذ بي في فلسطين» (منشورات أوليف برانش ــ 2020) الفريد كتبت: «لقد تبلورت فكرة هذا المؤلف أثناء تناول فنجان من القهوة في رام الله، وعملية إتمامه لم تكن علمية أو صارمة. لقد تواصلت مع أشخاص من مختلف أنحاء العالم متزوجين من فلسطينيين، أو عاشوا في فلسطين لفترة طويلة، أو لديهم خبرة طويلة وعميقة في ما يتعلق بفلسطين، فوجدت نفسي أبحث عن نوع معين من «الأجانب»، النوع الذي يدرك أنه في ظن العديد من الفلسطينيين يعني «الذين يستفيدون من معاناتهم». أشير إلى هؤلاء المتخصصين في المساعدة الدولية والدبلوماسيين الذين تحركهم الاهتمامات المهنية أكثر من التضامن. إنهم يثيرون غضب الفلسطينيين. لكني أردت في المقابل تسليط الضوء على قصص الأجانب الذين عملوا بجدّ وبتواضع وصدق لأجل الفلسطينيين ومعهم. هم نوع مختلف من الأجانب الذين يمكن أن يصبحوا جزءاً من المجتمع الفلسطيني ويتغيرون بواسطته. بعض من دعوته اعتذر عن عدم المشاركة وقال: على الفلسطينيين التحدث عن أنفسهم، لكنهم ساعدوا باعتذارهم هذا في تشكيل رؤية المشروع واتجاهه. «وإذ بي في فلسطين» ليس مؤلفاً عن فلسطين، وإنما مجموعة من تأملات غير فلسطينيين تعتبر قصصهم أيضاً هدية من هذا المكان».

وجهات النظر الـ 22 الممثلة في هذا المؤلف تعكس آراء كُتَّابها، وهي مجموعة معبرة وغنية بالمعلومات ومأساوية ومناصرة ومدهشة وعالمية، لكنها لا تستطيع أبداً رسم صورة كاملة. تجارب الأجانب تتغير باستمرار، والمحررة نورا مراد تقول: «لا أستطيع أن أتخيل فلسطينياً يقول اليوم: إن الإغلاق أو حظر التجول هو خطئي لأنني أميركية، مع أنه بالتأكيد أكثر صحة اليوم مما كان عليه في أي وقت مضى. لقد عانى الفلسطينيون عقوداً من الاستهداف على أيدي الأجانب، لكنهم شهدوا أيضاً عقوداً من التضامن». «وإذ بي في فلسطين» مجموعة من الروايات من مختلف القارات التي تستكشف مفهوم كونك أجنبياً في ما يتعلق بفلسطين، جنباً إلى جنب مع الشعب الفلسطيني الذي يتم تصويره على أنه أجنبي في أرضه. بالنسبة إلى الفلسطينيين، للغربة معانٍ مختلفة. المستوطنون هم الأجانب الذين يشاركون في سرقة فلسطين ويجعلون الفلسطينيين أجانب من خلال التهجير. هناك أيضاً الأجانب الذين يتعاملون مع الشعب الفلسطيني، وكذلك «الأجانب المحترفون الذين يأتون إلى هنا ويبنون وظائف على حساب نضالنا».

يجمع المؤلف مجموعة من القصص من أشخاص تتشابك حياتهم مع حياة الشعب الفلسطيني بطرق مختلفة. ومحررته، نورا لستر مراد، وهي أميركية متزوجة من فلسطيني، كتبت في مقدمتها «الفلسطينيون مجتمع منفي، لكن الكُتَّاب الذين ظهروا في هذه المجموعة ليسوا كذلك»، وتشرح كيف بيّنت مجموعة الروايات المباشرة عن الأجانب للفلسطينيين «ليصبحوا جزءاً من المجتمع الفلسطيني ويتغيروا بواسطته».

قصص الأجانب الذين عملوا بجدّ وبتواضع وصدق لأجل الفلسطينيين ومعهم

تم سرد تجارب مختلفة في هذا المؤلف. يعتزّ البعض بالتقاليد والالتزامات الاجتماعية للانضمام إلى عائلة فلسطينية. بالنسبة إلى الأجانب الآخرين الذين يتزوجون من عائلات فلسطينية، يُنظر إلى التقاليد على أنها خانقة ومتناقضة مع ثقافة وطن الآخر. على سبيل المثال، تقول البوليفية كورينا ماماني، التي تعيش في فلسطين منذ 25 عاماً: ترتبط التقاليد والثقافة بالضغط الاجتماعي. لكن سميرة الصفدي، وهي ألمانية من أصل فلسطيني، تتماهى مع فلسطين وكونها فلسطينية على مدى فترة طويلة من الزمن. «لا أستطيع أن أقول إنني فلسطينية عندما لا أشعر أنني كذلك». بالنسبة لها، لم تكن الثقافة الموروثة هي التي روّجت للهوية، بل بالأحرى تجربتها في العيش في فلسطين والاجترار حول هذه الفترة بعيداً عن فلسطين في بلغاريا. «العيش في فلسطين له معنى الآن. إنه يعني صموداً ومقاومة».

تجربة معاكسة تماماً لتجربة فلسطين من المنفى قدمتها الفلسطينية التشيلية نادية حسن، التي شكل سعيها للعودة إلى وطنها بعد تجربة في الجامعة معنى لمفهوم «العودة». بعد العديد من المحن، تمكنت من جعل

فلسطين منزلها.

في أوقات أخرى، تؤكّد العادات والتوقعات المجتمعية الفلسطينية الغربة، كما في حالة زينة، وهي امرأة سودانية متزوجة من أرمل من الولايات المتحدة. تقول عن دورها المهني في عيادة السرطان: «إنهم يرون في

مقدمة رعاية، وامرأة، وأم أخرى تشعر بألمهم».

بالنسبة للأشخاص الذين لم تطأ أقدامهم فلسطين أبداً، والذين تعتمد معرفتهم أساساً على الأخبار والتحليلات، فمن السهل بناء مفهوم محدود عن الفلسطينيين وماهية فلسطين. من خلال روايات مثل هذه، أصبحت إنسانية السكان المستعمَرين ملموسة، ولم يعد يُنظر إلى الفلسطينيين على أنهم بند في الأخبار أو جدول الأعمال الدبلوماسي فقط.