This article first appeared in Cornerstone, the newsletter of the Sabeel Ecumenical Liberation Theology Center, Issue 72, Summer 2015, pp. 12-14.

Global citizens who care about justice often complement their social activism with financial gifts to organizations they believe in; and they often support their government’s use of tax funds to provide bilateral aid to developing countries. “Aid” means “help” and good people want to be helpful. They give from a sense of obligation, which is often grounded in faith, and in response to the opportunity to make a positive difference in the world.

Palestinians are among the highest recipients of international aid from governments and have been for decades, making them among the most aid-dependent peoples in the world. While most of us would consider aid a good thing, it is obvious that being dependent on aid is a bad thing. But the majority of concerned global citizens don’t realize just HOW bad it is. If they did, they would make aid accountability a priority among their Palestinian solidarity activities.

Palestinians are among the highest recipients of international aid from governments and have been for decades, making them among the most aid-dependent peoples in the world. While most of us would consider aid a good thing, it is obvious that being dependent on aid is a bad thing. But the majority of concerned global citizens don’t realize just HOW bad it is. If they did, they would make aid accountability a priority among their Palestinian solidarity activities.

On one level, the problems with international aid in Palestine are just like the problems with aid that are reported in many parts of Africa, Latin America and Asia – aid is unpredictable and uncoordinated; it reflects priorities of donor countries not necessarily the recipients; it distorts the agenda of local governmental and civil society groups; it undermines accountability to communities in favor of bureaucratic accountability to donor institutions; much aid is repatriated back to donor country economies; and aid is often wasted on consumption and activities that don’t lead to real, long-term development.

Because of these problems, and because of the dialogue around the expiration of the Millennium Development Goals, activists in aid-recipient countries are working together to protest both the methods and the politics of international aid. They are moving beyond a technical critique that implies that we just need more aid, more transparent reporting, more harmonized procedures, and better use of data about what kind of development works. Instead, they are talking about “development justice” and integrating aid issues with other aspects of global inequality such as third world debt. Some are even talking about aid as a form of neo-colonial intervention designed to maintain inequality rather than challenge it and suggesting that poor people reject aid.

In Palestine, aid is such a prominent and visible part of life that even non-experts tend to be quite sophisticated about how it works. Perhaps this is because nearly everyone is directly or indirectly supported by aid. The largest employer, the Palestinian Authority, can’t pay salaries without international aid, and the Palestinian elite and middle class (upon whom the consumer and service industries depend) are nearly all employed by United Nations agencies, international non-governmental organizations or local non-governmental organizations that depend on grants from the internationals. There is really no part of the economy or aspect of life that isn’t affected by international aid.

For this reason, it doesn’t take long for a conversation about aid among Palestinians to turn to a gripe session. Unfortunately, complaining isn’t very effective in making change. Some people feel they should be grateful for donors’ generosity, so although they aren’t happy with aid, they silence themselves. Some people are fearful that if they complain, donors will stop giving, so they only make vague suggestions that can’t be implemented. Others talk about the problems with aid, but don’t address their complaints to the right parties, or don’t understand how to frame their complaints in terms of rights, so they aren’t taken seriously.

To help Palestinians understand the aid system and their rights in it, a group of Palestinian and international activists are launching Aid Watch Palestine, an initiative to start a conversation about aid that is honest, critical and constructive. We want to connect the issue of aid with the struggle for national liberation and with human rights.

For example:

- If Israel is responsible under international humanitarian law for rebuilding Gaza, why are the international donors paying, thus letting Israel off the hook completely for the costs of their damages?

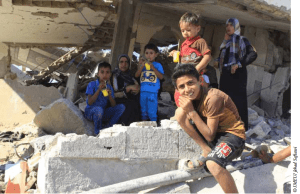

- If international actors are intervening because of a humanitarian imperative, how can they justify the shamefully slow pace of rebuilding in Gaza?

- If international actors truly wish to prevent further violence, why do they allow Israel to profit so much from occupation and war?

- How can international actors credibly claim to be helping while they are simultaneously supporting the Israeli war machine?

By posing questions like these to Palestinians, aid actors and global citizens, Aid Watch Palestine hopes to challenge people who say, “We are doing the best we can under difficult circumstances.” We want to challenge ourselves to think more creatively about how international intervention can actually help – not by throwing money at the problem, but by addressing root causes of the conflict and further long-term solutions that respect human rights and international law.

Wanting to help isn’t good enough. After 67 years of “aid,” Palestinians are still occupied, dispossessed and colonized and vulnerable to violence, poverty and hopelessness. Where is the accountability? Concerned global citizens should still give, but we think they should ask harder questions about their government’s aid programs:

- Is aid intended to further the donor government’s foreign policy objectives? Or is it intended to respect the priorities, rights and agendas of recipient communities?

- How are decisions about aid allocations made? Who makes them? Who chooses the decision-makers?

- Does aid only address the symptoms of suffering or does it address the root causes, fundamentally changing power relations?

- What kind of global economic and political system is advanced by international aid and is it contributing to the kind of world we want to live in?

We also need a critical approach to our own charitable contributions:

- Are we giving to international organizations when there are local organizations doing the same work? If so, why are we doing that, and what impact does it have on the capacity for local self-reliance?

- Are we giving to “emergency” needs (like food aid) instead of to longer-term (and harder) efforts to prevent food insecurity in the first place? If so, are we being fooled into supporting simplistic and ineffective approaches?

- Are we making charitable contributions when what is really needed is our political intervention so that we can find just solutions? If so, how can we combine ever act of financial giving with a call to a representative, letter to the media, or public statement of support for a government policy that will lead to self-determination and peace with justice?