A lovely conversation with Areen Bahour at Brookline Booksmith on November 16, 2022. We talked about growing up #Palestinian, “Ida in the Middle” and the importance of books about Palestine for both Palestinian and non-Palestinian kids. (1:05)

Archives for November 2022

“YA Arab American novels: Bringing Palestine into our fictional world” by Nada Elia

This brilliant analysis of Palestinian children’s literature and teaching about Palestine includes a review of Ida in the Middle. It originally appeared in Middle East Eye.

One of the courses I regularly teach at my university is “Introduction to Arab American Studies”. Most students take it because it fulfills one of the university’s “diversity” requirements, not because they are invested in the topic.

We get to read about the strong sense of community that sustains Palestinians as they navigate life in these extremely difficult circumstances

For me, the course is a window into mainstream America’s glaring lack of exposure to any Arab-American issues in the K-12 curriculum. It has been sobering to realise that most Americans can go through their entire school education without reading a single novel, or social studies chapter, about the diverse Arab American communities that are part of the fabric of broader American society.

For most of my students, there are Arabs – swarthy foreigners living in inhospitable countries half a world away – but no Arab Americans; the doctors, teachers, cab drivers, grocery store owners and neighbours who may live next door to them.

They have even less awareness of the effects of US foreign policy in the Middle East and the experiences and stories this policy shapes among immigrants from these communities.

What it means to belong

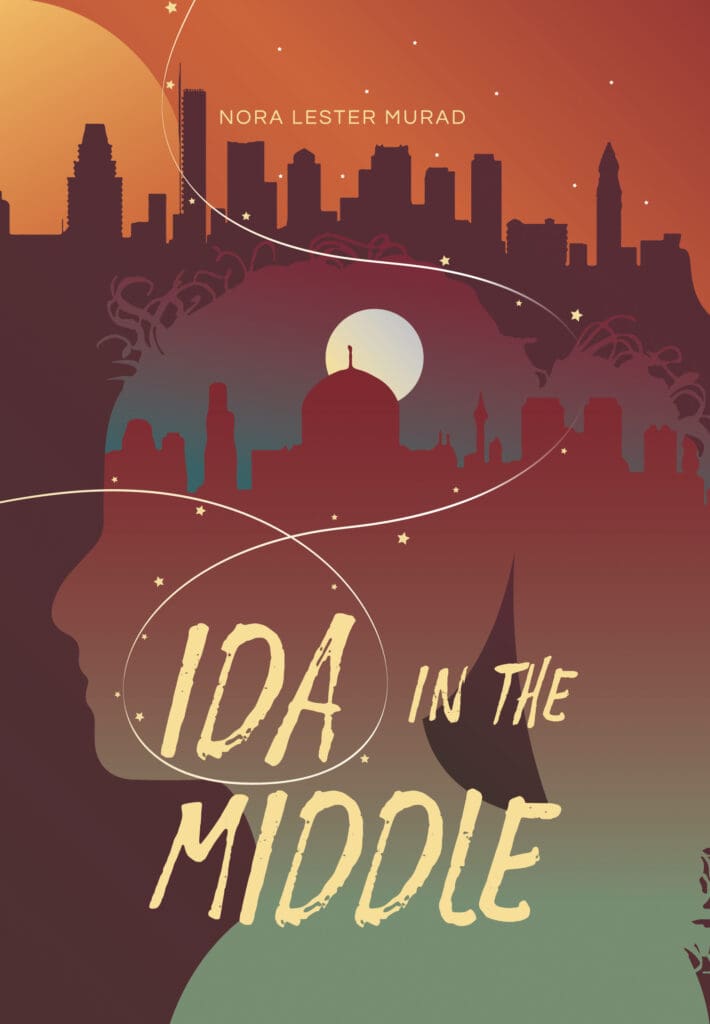

A new young adult novel, Ida in the Middle, by Nora Lester Murad, explores the deeply unsettling feeling that members of these communities’ experience, as they are told in both subtle and overt ways that they do not belong in the United States, even when it is the only country they have ever known.

In this debut novel for Murad, Ida, a bashful Palestinian American teenager, is dreading the final class project: discussing her “passion” with the rest of the class.

Her anxiety skyrockets when the school principal informs her that she will be representing her school in this eighth-grade capstone for the entire region.

She is terrified at the thought that someone in the audience will shout out “terrorist” as she ascends to the stage, just as someone had scribbled that insult on her school desk. Home alone one afternoon, as she worries yet again about that presentation, she reaches for her comfort food, green olives sent by her aunt all the way from Palestine.

Olives, as every Palestinian knows, are not just a savoury snack; they encapsulate our culture in each dense nugget. When they are cured by a favourite aunt, they can have magic powers. As she eats the olives, Ida is transported to her parents’ village, Busala, just outside Jerusalem, where she immediately feels at home.

In this alternate reality, her parents have never left Palestine, and she has grown up with feelings of belonging amid kids who look like her, speak Arabic, and can pronounce her name correctly: ‘Aida, with an ‘ayn.

But life in Busala is also unpredictable, scary, and dangerous because of Israel’s occupation. Here, Murad skilfully weaves the narrative between Ida’s fantasy and the all-too-real events of life under occupation, as Ida has to brave Israeli military raids, curfews, and home demolitions.

We get to read about the strong sense of community that sustains Palestinians as they navigate life in these extremely difficult circumstances. We witness the immense courage of Palestinian children – including Ida herself – as they dodge the occupation forces; and we hear discussions about survival and resistance, including the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement.

There are some exhilarating moments, such as when Ida carries a terrified three-year-old boy to safety, telling him his name, Faris, means “knight,” and that he is their leader, while he explains that her name means “Returning,” and he knows she will not leave him behind, as she scouts their whereabouts for a safe path home.

And there are heartbreaking moments, as when Ida watches Israeli bulldozers demolish her friend Layla’s family home. This experience transforms Ida and, after having eaten more green olives, she is transported back to Boston, where she gives an impassioned presentation about the hardships that Palestinians endure under Israel’s settler colonialism.

A resource for educators

As I put down the novel, I went over to the website that accompanies it, and where Murad, a longtime educator, has compiled a wealth of useful teaching resources. Murad addresses questions that other educators may have as they teach a novel about Palestine, linking to dozens of websites categorised by who compiled them (e.g. librarians, the Institute for Palestine Studies, the Middle East Children’s Alliance, and many more).

There are lesson plans, Palestine-centric resources, resources about the Middle East and Muslim issues, and more valuable information than any book review can do justice to, all superbly organised and easy to navigate.

In his endorsement of the book, publisher Michel Moushabeck wrote: “I have been waiting for this YA novel to be written since I founded Interlink 35 years ago.”

As for me, I can enthusiastically say this is the resource website I’ve been waiting for. But please don’t take my word for it, explore it for yourselves. Whatever your level of knowledge about Palestine, there will be something for you there.

A seasoned activist, Murad knows there will be pushback against her novel. Ida in the Middle reminded me of Ann Laurel Carter’s The Shepherd’s Granddaughter about a young girl whose family home near Hebron is being threatened by encroaching Jewish settlements. The book won eight awards, including the Canadian Library Association Book of the Year Award for Children, and the Society of School Librarians International Best Book Award.

But the Zionist advocacy group B’nai B’rith objected to what it described as its “anti-Israel propaganda”, and the novel has not been included in any Canadian school curriculum.

Will Ida in the Middle suffer a similar fate because it mentions Israel’s demolitions of Palestinian homes – an absolute reality, yet one of Israel’s many crimes that are apparently taboo in American discourse?

Pushing back

Murad was a speaker on the Boston Book Festival panel “Pushing Back Against the Pushback: Uplifting Marginalised Books for Young People in an Age of Censorship”, where she addressed the importance of assigning such novels in literature or social studies classes across the US, a topic she also discusses on the book’s website.

On the FAQ page, the author addresses her identity as someone who was not born Palestinian. One of the questions she answers is: “You’re not Palestinian, shouldn’t people read books written by Palestinians?”

Her answer is an unequivocal “Yes”, and she lists some of the Palestinian authors she recommends: for children, Randa Abdel-Fattah, Ibtisam Barakat, Ahlam Bsharat, Susan Muaddi Darraj, Sonia Nimr, Naomi Shihab Nye, and Wafa Shami, among others.

For adults, some prominent fiction and non-fiction writers available in English are Susan Abulhawa, Hala Alayan, Ghassan Kanafani, Sahar Khalifeh, Edward Said, Adania Shibli, among many, many others.

Educators have no excuse not to assign the wonderful books available to them about young Arab Americans

Murad herself is married to a Palestinian, lived in Palestine for 14 years, and mothered three Palestinian girls. Her sensitive portrayal of Ida is certainly that of a loving parent, steeped in Palestinian culture not as a tourist, but as an engaged member of a Palestinian family.

Given her background, it is perhaps not a coincidence that the protagonist in Murad’s novel, like Susan Muaddi Darraj’s fabulous series, Farah Rocks, and The Shepherd’s Granddaughter, is a young girl, rather than a boy.

Certainly, girls need all the empowerment they can get in our exceedingly misogynist, patriarchal world, and these books offer that needed boost. However, my wish is for the next YA novel about a Palestinian American child to feature a boy, even as I fully appreciate the present offerings, and would welcome more.

But a lack of narratives around young boys being sensitive, caring, or protective of their friends and siblings could inadvertently risk perpetuating the myth that Palestinian girls are redeemable, while Palestinian boys are always dangerous.

For now, however, educators have no excuse not to assign the wonderful books available to them about young Arab Americans. And with the holidays fast approaching, everyone can push back against censorship by gifting precisely those novels that artfully inject our cultural and political experiences into the broader American landscape.

Nada Elia teaches in the American Cultural Studies Programme at Western Washington University, and is currently completing a book on Palestinian diaspora activism.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.

Rockstar Palestinian Educators Discuss Teaching Palestine in US schools

A #MustWatch presentation! The Palestinian Museum US in Connecticut hosted a launch of “Ida in the Middle” and Luma Hasan, Sawsan Jaber and Mona Mustafa talked about the experiences of Palestinian students, Palestinian teachers and the challenges of teaching Palestine in US schools.

Censorship of Palestinians is So Normal, Even Antiracists Don’t See It

This guest post exploring censorship of Palestinian children’s books was first published on Betsy Bird’s blog on School Library Journal.

I started researching censorship of Palestinian children’s books out of concern that my forthcoming young adult novel, Ida in the Middle, could be attacked or banned because the protagonist is a Palestinian-American. Ida is an 8th grader who faces ridicule and bullying at school and finds her strength by connecting with the struggle for self-determination happening in Palestine. Ida’s experiences in her Massachusetts school are loosely based on my youngest daughter’s junior year about which she says, “I didn’t feel like they kicked me out because they had never included me in the first place.” I later spoke with many Palestinian kids with shocking stories of racism, exclusion and invisibility in US schools all of whom thought they were the only one – because no one talks about anti-Palestinian racism.

Palestinians aren’t on the radar of most advocates for marginalized books

What I’m finding in my research about censorship of Palestinians is concerning. Although advocates of intellectual freedom, freedom to teach and the right to learn stand up (appropriately so!) for books about Black, brown and queer communities, the intense, multilayered censorship of Palestinians goes virtually unchallenged – and, in fact, unnoticed. Simply put, Palestinians and their literature are invisible to organizations like the American Library Association, National Coalition Against Censorship, and the National Council of Teachers of English, among others. A good example of this is PEN America’s oft-cited report, America’s Censored Classrooms, which doesn’t even mention Palestinians, although there is a barrage of legislation targeting them, and overwhelming documentation of censorship of Palestinians.

For example, earlier this month, Independent Jewish Voices (IJV) released a detailed, 97-page study of harassment, intimidation and repression against Palestinians in education that includes interference in hiring, classroom surveillance, restrictions on campus groups, demands for the censure or dismissal of pro-Palestinian faculty and students, and obstruction of pro-Palestinian events. They found that the constant and increasing harassment creates a “chilly” environment which threatens academic freedom, muzzles scholarly production, obstructs academic careers, encourages mendacious and malicious discourse, and stifles legitimate protest. More than that, they paint a picture of life for many Palestinian teachers and students that is painful and unfair.

The IJV report focuses on Canadian higher education. Here at home, Palestine Legal, a Chicago-based nonprofit co-published a study with the Center for Constitutional Rights in 2015 called, “The Palestine Exception to Free Speech” showing the same tactics are used in the United States. In nearly 100 pages and with accompanying videos, they explore a range of silencing tactics that are pervasive across US higher education institutions, including monitoring and surveillance, falsely equating criticism of Israel with antisemitism, unfounded accusations of support for terrorism, official denunciations, bureaucratic barriers, administrative sanctions, cancellations and alterations of academic and cultural events, threats to academic freedom, lawsuits and legal threats, and more. In the US, as in Canada, simply being Palestinian seems a provocation, which is hard enough for adults, but imagine being a Palestinian student facing this type of racism in school?

Information about attacks on Palestinians in education is anecdotal but abundant

Although no one seems to be systematically tracking the impact of censorship of Palestinians in K-12 education in the US, there is abundant evidence of harassment aiming to censor Palestinian and pro-Palestinian voices. For example, the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Consortium (LESMCC) has been slapped with a lawsuit because of their inclusion of Palestinians in the curriculum, and teachers not limited to the LESMCC teachers are experiencing administrative harassment in the form of tens if not hundreds of public records requests, not to mention threats to individuals and institutions.

In a separate incident, Palestinian-American teacher, Natalie Abulhawa, was fired from a private, all-girls school called Agnes Irwin for social media posts that were nearly a decade old and were found on a known Islamophobic site, according to the Council on American Islamic Relations.

Attacks on Palestinian books also happen. In a well-known case, a NY bookstore was attacked for their support of the picture book P is for Palestine (Bashi Goldbarg, self-published), and a Hannukah reading of the book organized by anti-zionist Jews was attacked by right-wing Israel supporters.

More recently, Kayla Hoskinson, a librarian in Philadelphia was disciplined for an antiracist post that mentioned Rifk Ebeid’s picture book, Baba, What Does My Name Mean? (self-published) and references to Ebeid’s book and the works of Palestinian poet laureate Naomi Shihab Nye were censored.

Another recent library censorship case occurred in San Francisco over ideas about Zionism and racism. San Francisco Public Library canceled an art exhibit and public event when organizers refused to remove text that ACLU lawyers said was protected by the First Amendment. The library’s explanatory statement said: “… the Library retains the right to determine the suitability of any proposed exhibition to be included in the Library’s exhibition program. The Library also reserves the right to reject any part of an exhibition or to change the manner of display.” But if a library has the right to reject any part of an exhibition, they also have the right to include it, despite pressure from politically-motivated interest groups.

Librarian Kayla Hoskinson talks about the chilling effect of this kind of censorship.

“Attacks against librarians and teachers for including Palestine in their curriculum are definitely noticed by our colleagues. Some are unafraid to move forward with me to plan and host programs about Palestine. More colleagues, though, see what happened to me and don’t want the trouble. Even if they agree, they know they will not be supported against attacks. ALA really needs to re-develop policies and guidelines about neutrality in the field.”

Very few children’s books about Palestine are being published

But when it comes to traditional bans–the listing of books that are forbidden in schools and libraries–attacks on Palestinian books seem more opportunistic and ad hoc rather than systematic and ambitious like the ones directed against Black, brown and queer books.

This may be because there are so few books about Palestine. For example, the Diverse Book Finder studied over 2000 picture books published since 2002 and found only 3% fell into the broad Middle Eastern category. How few of those are Palestinian?

In a study I’m currently doing with several Palestinian teachers to produce a framework that educators and librarians can use to evaluate books involving Palestine, we found that a full 40% of our sample of books about Palestine authored by Palestinians were self published, indicating that censorship is happening before publication. This means that fantastic children’s books like Tala Fahmawi’s self-published Salim’s Soccer Ball get only limited visibility and lack the library-attractive credibility that comes along with being traditionally published.

Sadly, the problem is not merely one of oversight or negligence. In a webinar called “Translating Palestine,” translator Sawad Hussain said she had been told outright by some editors that they are afraid to work with Palestinian authors lest they be seen as too political or publishing “too many Palestinian authors.” Translator Marcia Lynx Qualey said that even books accepted for publication are often “bulletproofed,” which she described as scrubbed of content Palestine’s opponents would claim is offensive.

Palestine is a taboo topic due to fear and politicization

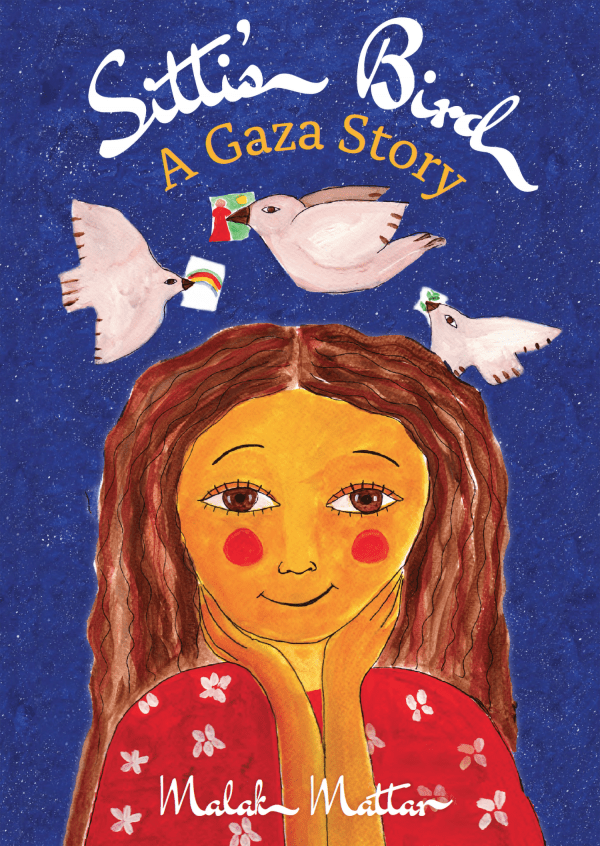

My publisher, Interlink Books, founded by Palestinian-American Michel Moushabeck has provided a much-needed pathway for Palestinian books and books about Palestine to reach US readers, yet he too has faced challenges. Most recently, Malak Mattar’s Sitti’s Bird: A Gaza Story (2022) has been unable to get a single mention or review in trade publications and mainstream media, unlike all the other picture books he’s published. Moushabeck says, “It’s because it’s a Palestinian story of trauma. We knew this would happen because the same thing happens to all our titles written by Palestinians. Some editors do not assign books by Palestinians for review–especially ones they deem controversial or think can get them into trouble.”

The consequences of the censorship of Palestinian children’s books goes far beyond the impact on Palestinian authors and Palestinian children. As the ALA’s Unite Against Book Bans campaign says, without books:

“Students cannot access critical information to help them understand themselves and the world around them. Parents lose the opportunity to engage in teachable moments with their kids. And communities lose the opportunity to learn and build mutual understanding.”

American Library Association

Applying principles of intellectual freedom, freedom to teach and the right to learn to Palestinian topics

For the ALA and other librarians and educators who advocate for intellectual freedom, freedom to teach and the right to learn, Palestine should be with others at the frontline of the struggle. Some even argue that Palestine is the litmus test of antiracists’ commitment to rights for all. For this reason, I hope organizations like the American Library Association, the National Coalition Against Censorship, PEN America, the NCTE and others who librarians and educators look to for leadership will become proactive in rejecting the violent silencing and criminalization of Palestinian voices. I hope they will step forward to demand intellectual freedom, the freedom to teach and the right to learn not only for some, but for those who most need to be uplifted in order to be heard, including Palestinians.