This 30-minutes conversation is a warm exchange about the complexities of living in relation to Palestine for Palestinians who live in the diaspora and non-Palestinians who have joined the community (like me!). Aline Batarshe, Executive Director of Visualizing Palestine, Besan Abu-Joudeh, Founder of Build Palestine, and I speak personally about the challenges and joys of staying being part of the Palestinian struggle for visibility, dignity and rights in the United States.

Archives for October 2022

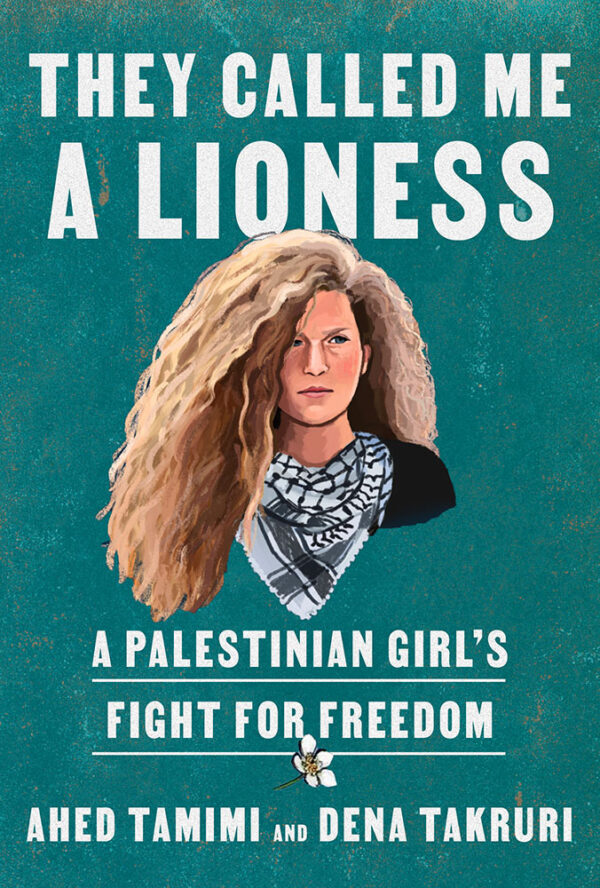

Interview with Ahed Tamimi, an Icon of the Palestinian Resistance

This review of They Called Me a Lioness and interview with Palestinian heroine Ahed Tamimi and Dena Takruri was first published by The Markaz Review.

They Called Me a Lioness: A Palestinian Girl’s Fight for Freedom; memoir/biography by Ahed Tamimi and Dena Takruri; Penguin Random House 2022; ISBN 9780593134580

By Nora Lester Murad

Ahed Tamimi and Dena Takruri’s book, They Called Me a Lioness: A Palestinian Girl’s Fight for Freedom (One World, 2022) quotes an Israeli interrogator trying to coerce information from stoic, 16-year-old Ahed: “Who? Is your father behind you? Or is it your mother who’s behind you?” “Who? Who is behind you?”

In 2017, Ahed was charged with assaulting an Israeli soldier, though family members point out that she wasn’t arrested until the video went viral, so she was most likely targeted because she humiliated the Israeli government.

Once the video of Ahed slapping and kicking a soldier went viral, two previous videos of her standing up to soldiers in her West Bank village of Nabi Saleh got new circulation, including one of 11-year-old Ahed threatening soldiers after her big brother was arrested and one of 14-year-old Ahed biting a soldier who attacked her little brother.

Ahed had become a heroine, not only in Palestine, but around the world.

When I talk to Ahed, she deflects all questions about herself, always using the pronoun “we,” referring to the collective Palestinian people.

“A reluctant heroine,” Dena Takruri corrects me when we talk about her experience co-authoring the book. “It was never about her. It was about the message.”

It’s true. When I talk to Ahed, she deflects all questions about herself, always using the pronoun “we,” referring to the collective Palestinian people. (We spoke in Arabic, with me apologizing several times. I recorded our interview and my husband, who is Palestinian, translated it with me.)

“‘Hero’ is a big word,” Ahed says, “and it comes with lots of responsibility. You can’t just say it casually. It’s a word that can change your life. But all of us in Palestine are heroes. We all live under the same occupation, the same injustice, and we all resist. Every single one of us is a hero inside, and that hero comes out when the time is right.”

Ahed’s videotaped interrogation shows the Israelis finally realized the threat posed by the heroine Ahed Tamimi. They were no longer laughing the way they did when she fake punched soldiers at age 11.

Though only 16 at the time, she was interrogated without the presence of her parents, lawyer, or even a female soldier. They inappropriately commented on her appearance and threatened her family and friends, but Ahed refused to talk.

“Who? Is your father behind you? Or is it your mother who’s behind you?” “Who? Who is behind you?”

The interrogators could not have known the significance of their question.

If the Israelis were to read Ahed and Dena’s book, they would understand that behind the lioness, Ahed Tamimi, stands an entire pride.

“Ahed mentions many girls and women in the book, and she credits all of them for their resistance and for enabling hers,” Dena continues.

I ask Ahed who is behind her, and her voice gets even stronger.

“Behind me? Behind me is the natural response to occupation — to reject it. Behind me are my mother and father who taught me to resist the occupier, and my grandmother who instead of telling me fairy tales about Layla and the wolf told me stories about how to resist the occupation. Behind me are the people all around me, the people I love, who I can lose in any minute. Behind me is an entire generation that I don’t want to live through the same experience that I did.”

Ahed is proud of her pride.

Nariman, Ahed’s mother, has been arrested more than six times and has held the family together during her husband’s more than nine arrests. Nariman was arrested and served eight months along with Ahed for incitement, since she filmed and shared the video of Ahed that went viral.

“If I hadn’t seen my mother demonstrate, get arrested, and be wounded, maybe I wouldn’t have done what I did and maybe my brothers and I wouldn’t be the way we are. Seeing my parents confront the soldiers helped us to believe that like them, we can defend our land and our country,” Ahed says.

Then she quickly adds: “But all Palestinian mothers are like mine, and all Palestinians are like us. Of course, there are some people who are controlled by fear. But most people are active and do things to resist the occupation, and this is not limited to our village, Nabi Saleh. Nabi Saleh just gets more media attention. But really, the same thing that is happening in Nabi Saleh is happening all over Palestine.”

Marah, Ahed’s best friend and cousin, was beside her throughout her growth. In the book, Ahed described how Marah was there at age six when the two girls joined a large group of kids running away from Israeli soldiers to Marah’s house where they packed themselves in a closet trembling in fear, only to tumble out onto a soldier’s combat boots when the house was searched. She was still there a decade later, the day Ahed emerged from her eight months in jail to a heroine’s welcome.

Janna Jihad, Ahed’s younger cousin, started reporting from Nabi Saleh and Palestinian cities across the West Bank when she was just seven years old. She has amassed hundreds of thousands of supporters across various social media channels. In the book, Ahed says, “The sight of an innocent little Palestinian girl reporting on the suffering of other children and adults under occupation moved people. It compelled them to open their eyes to the countless injustices perpetrated by Israel.”

Ahed credits Palestinian activist, academic and elected representative Khalida Jarrar, who taught classes to all the young Palestinian girls in prison, for her successful graduation from high school. More importantly, she credits Khalida for helping her develop a larger vision and strategy for Palestinian society. In the book, Ahed says:

We must ensure that when we finally do achieve liberation [from Israel], we’re not left with a society that’s full of corruption and inequity. It’s imperative that we fight for women’s rights, to ensure that we have full equality between women and men. We need to get rid of traditional mentalities that judge girls and women through the lens of shame. We also need to fight for better employment opportunities for our youth and find ways to get them involved in the political process. Why should those holding political office be predominantly old men? They’ve consistently proven themselves incapable and irrelevant.

Ahed’s aunt, Manal, an early and consistent leader in Nabi Saleh’s popular resistance, has been arrested multiple times, shot, beaten and strip-searched, yet she continues to speak out about feminist resistance.

Even Ahed’s grandmother, Tata Farha (to whom the book is dedicated), features prominently in her political development. In the book Ahed says:

Tata Farha’s bedtime tales were all real-life stories that taught us the history of our family, of the village, and of Palestine. Many reflected the hell and heartbreak she and our people had lived through. All of her stories were educational. They not only shaped my imagination, but also revealed to me the generational trauma that’s embedded in our DNA.

There was no way I could get Ahed to speak about herself or acknowledge anything significant about herself, her family or her village. Even when I asked about the challenges of being labeled a hero, she gave others credit, uplifting those around her.

“Maybe in other parts of the world, people get upset and they go to a psychologist. For me, I don’t go to a psychologist, I go back to the people who understand me because they are living the same experience and they have seen it and already know all the details. They stand by me and help me more than anyone else. I get my strength from them. Wherever I go, I find them next to me.”

After all she’s been through, she still has hope. Ahed lifts everyone’s spirits. —Dena Takruri

Even if Ahed won’t admit it, there is something particularly inspirational about her. I ask Dena, who has spent years following Ahed and countless hours co-writing the book with her, to explain what it is.

“As a journalist, I’ve interviewed many people, and it’s rare that I feel electrified. It’s her poise, conviction, power and strength. After all she’s been through, she still has hope. Ahed lifts everyone’s spirits.” Dena Takruri, a prominent journalist and proud Palestinian in her own right, has also become part of Ahed’s pride, standing with her to protect the group and its territory. The book they’ve co-written is a kind of roar, one that the rest of us creatures in the forest would be smart to heed.