These days, I delete all emails related to writing and publishing. I work fast to avoid being intrigued by subject lines. With each click I feel a millisecond of clarity (nothing is more important than family), but the swishing sound of the trash emptying makes my chest tighten with something like grief: I have lost the joy of writing, at least for now. All I write these days are emails about treatment modalities and appeal letters to insurance companies.

Not long ago, however, I forced myself to read a blog post about book promotion because, while I do not have the energy to care much, my first book will be released in a few months; and I owe it to those who supported me to try to make the book successful.

With my guard down, I lost myself in the practical minutia of soliciting book reviews when I came across a sentence that started: “I am OCD, so I research every opportunity….” The casual reference to OCD upset me terribly. I wrote immediately to the writer of the article: “OCD is not being detail-oriented or hard working. It is a debilitating mental illness caused by a brain dysfunction.” Neither the writer of the post nor the blogger who hosted it wanted to write a retraction or clarification (although the offending sentence was removed from the online version). I understand completely. Being a regular person with imperfections can interfere with the trajectory of a writer’s “success.”

But the fact remains: There is such a thing as being “paranoid” (with a lower case p), that is not at all the same as being “Paranoid” (with a capital P). People suffering from mental illness and their families are harmed when we don’t recognize the difference. Even though every mental illness is different and every person’s experience of mental illness is unique, I know this much from my own personal experience.

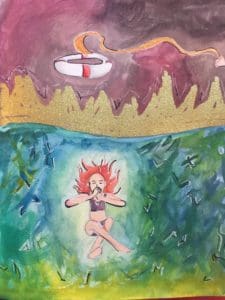

My 14-year old has Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and our lives revolve around it, are controlled by it, and are hurt by it in deep and inexplicable ways. There is no facet of her life or mine that is untouched by her OCD. Still, she is not OCD. She is a person with an illness, not the illness itself. Not making the distinction between the person and illness – explicitly and repeatedly – does harm. Therapists even suggest that kids name their OCD to remember that they are not their illness. My daughter’s OCD is named Jarrad. When my daughter has intrusive thoughts (constant, negative, terrifying thoughts that are completely involuntary), I remind her: ‘That is not you. That is Jarrad trying to trick you into doing compulsions. You must believe that you have the power to tell him to shut up.’”

I have read that most people who suffer from OCD know very well that their thoughts and behaviors are irrational (unlike sufferers of some other mental illnesses), and because they are ashamed, they often go through extreme measures to hide their symptoms. People close to them may think they are quirky or weird, but often don’t realize there is a problem until it interferes with daily living. At that point, OCD behaviors may be dismissed as a “phase.” They may be labeled as disobedient (“Why do you insist on always making us late?”) or considered weak (“Why can’t you just ignore those thoughts if you know they are irrational?”) For all these reasons, it is common for suffers of OCD not to talk about their illness and not get the help they need.

No one tells a person with a chronic, incurable, painful heart condition that they should “get over it,” but they often say just that to a person with a chronic, incurable, painful brain condition like OCD. No one would write, “I’m Congestive Heart Failure” when explaining that they can’t catch their breath at the top of a flight of stairs, but they don’t think twice about saying, “I’m OCD” when casually describing their tendency to aspire to perfection.

In fact, the whole family suffers when a loved one has mental illness. Since Jarrad pushed his way into our lives, more and more of my daughter’s time – and mine – is stolen by her anxiety and my need to either prevent it or respond to it. When she is compelled to remake her bed ten times so that someone at school won’t die or when she walks in a certain pattern up and down every aisle of a department store to prevent a bomb from falling, I get angry, overwhelmed and feel hopeless. I need and deserve the help of a community (and a mental health system!) that understands that my daughter didn’t choose to be sick. She’s not sick because I’m a bad mother. And she isn’t OCD! She is a complex, worthwhile, lovable, smart, funny, creative and fantastic person.

Sadly, it is common for people to belittle her suffering by saying, “Oh yeah, I have OCD too,” or “Take advantage of your OCD to do well in school,” or when they tell me that I’m lucky that my daughter has OCD because their kids don’t keep their bedrooms clean the way my daughter does. Or they say, “She looks just fine to me!” as if they know what’s inside her brain. She often thinks that no one will ever understand her. She isolates herself looking for safety. Her healing gets harder.

I don’t know what it feels like to have OCD (as my daughter reminds me several times a day), but I do know what it’s like to love someone who does. I know what it’s like to spend every waking moment trying to get us through each day without a crisis, organizing our lives around what I think she can or can’t handle, and then changing plans at the last minute if she’s had a particularly bad nightmare or if a particular smell has triggered a breakdown. I know what its like to reorganize my priorities so that health is more important than just about everything else I ever cared about.

Somewhere inside of me, there is still a passion for writing. But right now, I can’t concentrate enough to read the stack of novels next to my bed, much less to write my own. Instead, I read about OCD, about trauma, about therapeutic doses and co-morbidity. When I talk about what we’re going through I learn that nearly every single one of us is somehow touched by mental illness. So why did so many people ask, “Are you sure you want to write about your experience and share it with the whole world?” Why wouldn’t I? We have absolutely nothing to be ashamed of (and yes, my daughter did encourage me to publish this piece).

Nora Lester Murad is not a mental health expert. She is the mother of three amazing daughters, one of whom has OCD and related brain dysfunctions. She participates in a family support group run by the National Alliance on Mental Illness – New York (NAMI-NYC) and believes fervently in their efforts to end stigma. Her first book will be released in a few months but the sense of accomplishment she expected totally eludes her. Simply put: Some things are more important than writing and publishing right now.