Archives for July 2012

Another Chapter of Palestinian Olympic History

Amani Awartani, coach of the Palestinian Olympic Swim Team, told me this story with all the drama and intrigue of a Turkish soap opera, and it is my pleasure to share the inside story with you.

Amani:

“I left Palestine for Portugal on the sixth of June for the pre-Olympic open water contest. It was the first time Palestinians participated in such an event, because we don’t have access to our sea, so we can’t train in open water. It was very exciting.

I had asked a friend to look for people in Portugal to cheer for Palestine, and was thrilled when the Palestinian ambassador to Portugal, Mufid Shami, called me. He even came to the airport when I arrived, and the next day he came to my hotel and said how great it was to have Palestinians competing in Portugal.

At the beginning, I was frustrated. I am a very social person. I like to talk to people of different backgrounds. But the other teams don’t even say ‘hello’ – even if they’re sitting right next to you. The Russians stay together. The Spanish speakers stay together. There were some Arabs, but once you overcome the language and culture, there are still personality differences. I think some of the coldness was cultural differences, but some was the competitive environment. I tried to be nice, but in the end, you can’t care too much about the others.

FINA (the Fédération Internationale de Natation – the world governing body for the five Aquatic Disciplines of swimming, diving, water polo, synchronized swimming and open water swimming) delivered technical information about the swimming course. It was very nice meeting. Then, every day there were two rounds of training: morning in the pool and afternoon in the sea so the swimmers could learn the routes.

At one point, I met the Egyptians, who were very friendly and helpful. It was my first time in such a huge event. They told me I would have to get on the pontoon (a floating dock) with a feeding stick in order to feed Ahmed as he swam. I had no idea! The Egyptians kept saying, “They didn’t tell you about the rules?” I did read the rules, but didn’t see the feeding stick. It wasn’t mentioned. I guess they thought it was our 20th time, but it was our first time in open water. Everyone else had previous experience so they thought it was known. But I didn’t know the trainer had to be on the pontoon to feed the swimmer! Thank goodness the Egyptians told me!

I was panicking a lot because I didn’t know what I was supposed to be doing. I didn’t have a feeding stick. I had never heard of a feeding stick before. So Ahmed Gebrel, my swimmer, and I went downtown and were very inventive. I bought a fishing pole and attached a bottle with water tape to the stick part. We were very inventive.

The rules are that if Ahmed touches the feeding stick while in the water, he is disqualified. If I bump into another swimmer, he and I are disqualified. If I fall into the sea, I disqualify him immediately. Since the pontoon is in the middle of the sea and the swimmers are swimming around it, it’s bumpy. There were 61 trainers on the pontoon! There are five rounds in the pre-Olympic open water contest. Each round, the swimmers swim to us on the pontoon to eat, but thank goodness, they didn’t come as a group so it was a little less pressure. One of the Egyptians was kind enough to offer to sit next to me and make sure that I didn’t fall into the sea. I was scared like hell that I get would disqualified.

On the day of the competition, the weather was terrible, of course. It was raining in the morning and freezing. In water it was about 17 degrees. Lots of swimmers dropped out of the second round because of the cold. But Ahmed completed all 5 rounds. He came in 48th of 61. He was 5th in Asia. China was behind us. Hong Kong was behind us. I was so relieved to see him get out of the water. But it’s a huge place, and when he finished, he went off with the swimmers to land, and the trainers went to land after them. I went to the tent where he was supposed to be and I waited. I started worrying after half hour. I searched for him and asked everyone ther, but nobody had seen him or knew where he was.

I told the FINA personnel and volunteers to search. After more than 90 minutes a volunteer asked for me. I was holding back tears. I felt sick. Then they told me Ahmed was in the recovery area with hypothermia and all his sugar had burned off. They had to give him 2 kilograms of glucose. After two hours of treatment, and after they put his clothes in the microwave, he felt better. And I felt better.

Some people may be disappointed that we came 41st of 61, but it was a success! Ahmed finished the entire five-round competition, and that’s amazing. So many swimmers couldn’t make it and dropped out. But Ahmed finished 10 kilometers in freezing water without any fault. That’s nothing to be disappointed about!

Unfortunately, some things did happen that pissed me off. One person tried to use influence to put his son in as an Olympic competitor in Ahmed’s place, but he didn’t get away with it. There was also a mix up between FINA and the Universality people, so Ahmed was taken out of the 50-meter race that he’s been training for, and he’ll be swimming in the 400-meter race instead. We even had to change flights because of that. But Sabine, our other swimmer, will still swim in the 50-meter.”

From the 21st to 27th of July they train twice a day in Olympic village pools. The Olympic Solidarity Committee funds both swimmers and the Palestinian National Olympic Committee funds Amani. Ahmed will swim directly after opening on July 28. Sabine swims on August 3.

I’ll be watching and cheering for the Palestinian team. Will you?

Interview with Amani Awartani, part two

I have to be honest: I don’t like sports. I’m just not interested in watching other people play games. But Amani Awartani, coach of the Palestinian Olympic swim team, weaves a story of gender, international politics, cultural pride, and personal challenge. Through her eyes, I see the upcoming Olympics as a significant milestone for Palestinians and the rest of the world – and a lot of fun.

Did you know that Palestine was recognized by the International Olympic Committee in the 1930s? That Palestine is listed on the official website of the Olympic movement? That there is a Palestinian Olympic Committee?

In fact, this is the fifth time that Palestinians have taken part in the Olympics, the first being in 1998. Since Palestine isn’t a state, Palestinians have to compete in the World Championships that are held before the Olympics and win points that make them eligible as “participants.” Until now, all the Palestinian competitors have been swimmers.

“This is the first year we have a ‘qualified’ competitor,” Amani explains. Maher Abu Rmaileh from Jerusalem competes in Judo. She adds quickly, “You can still win a medal if you participate by winning points and are not considered a qualified competitor.”

Since there are Palestinians all over the world, I asked Amani if Palestinians in the diaspora can swim with the Palestinian team. “Sometimes we are contacted by Palestinians in the US or elsewhere who want to swim with us. It is allowed as long as they aren’t registered as swimmers in another country But generally we refuse, even if they might bring us medals. We want to give local people a chance first.” Her voice trails off as she adds, “Maybe later we could include them in the national team, but how could we support them without funding?”

Although she is coach of the Palestinian Olympic swim team, Amani doesn’t actually train the Palestinian competitors for the Olympics. Ahmed Gebrel, a Palestinian refugee in his twenties who lives in Egypt and Sabine Hazboun, who is only eighteen years old, have been living and training in Barcelona. “Sabine missed her Tawjihi, the last year of high school, in order to train,” Amani said, clearly proud of Sabine’s commitment. Expenses, including funding for their coaches, were provided by the Olympic Solidarity Committee. But next year they’ll have to raise funds themselves.

Amani tells the story with such enthusiasm, I nearly pulled out my wallet to make a contribution. In fact, I was so taken by her passion, I almost jumped onto the table at the Zaman Cafe in Ramallah where we were talking to do a little cheer.

“Although this is voluntary work, I want to do my job 100%. We’re a team. I want the team members to know I am always there for them. I tell them: ‘You swim, and I’ll take care of the rest,’” Amani says.

Amani’s own children enjoy swimming. Her son used to sneak into Jerusalem to swim, since he doesn’t have a permit, but he didn’t want to pursue it competitively. Her daughter enjoys recreational swimming, but is more serious about football and, more recently, ballet.

“Everybody has his own thing. As for me, I find it a tremendous honor for us to be standing in front of the world, recognized as Palestinians. It’s overwhelming.”

But the best part of this story is yet to come! Do you know what a feeding stick is? Check back here to find out.

Interview with Amani Awartani, Coach of the Palestinian Olympic Swim Team

Amani Awartani, Coach of the Palestinian Olympic Swim Team, smiles triumphantly as she recalls her first swim competition. Although in those days it wasn’t considered appropriate for girls to swim in mixed-gender competitions, she swam anyway. Amani came in first in freestyle and second in breast stroke.

Then came the first Intifada. “There were curfews. Everything was upside down,” she remembers. Amani was not able to pursue her swimming ambitions. She never competed again.

But no one can doubt that Amani is still an athlete. Besides her tall, strong physique, she oozes an enthusiasm for sports that is infectious.

“Swimming was new, then,” Amani reminisces. “There was a group of young men from Jerusalem who were instructors. They started teaching others how to train. For cultural reasons, men can’t train women, so that gave me an opportunity. I trained the women.”

Amani became a trainer when she was only eighteen. She also taught swimming to three and four-year-olds for two years. “They were sweet but exhausting,” Amani confesses.

Palestinian participation in the Olympics came later. A German man from FINA, the international governing body of swimming, visited the Palestinian Swim Federation, a post-Oslo volunteer organization that oversees swim training, the pools, sponsorships, and competitions. It was around 2007 or 2008. Amani joined the Palestinian Swim Federation.

Volunteers with the Palestinian Swim Federation learned how to put together a real training program. “Training is tailored for each race. For the 50 meter, you need speed, so you practice jumping, train for speed on land, speed in the pool. But for the 10K race, you need endurance. The training is different.”

According to Amani, people who swim for speed and people who swim for distance have different kinds of personalities. The speed swimmers have to deal with pain and the distance swimmers have to deal with exhaustion. Both have to be determined.

Even today, although the competitions are mixed, men and women train separately. And there are still many more boys than girls. “Overall, the sport of swimming still isn’t very popular in Palestine,” Amani laments. “One problem we have is that our pools are almost all outdoors. That means you can only train about three months each year. Even the few indoor pools—at the YMCA in Jerusalem and Bethlehem—aren’t good enough. They are only 25 meters long. There are no 50 meter pools anywhere in Palestine.”

There are rumors that the Palestinian Authority may build a 50 meter pool in Jericho and Amani hopes they’ll allow competitive swimmers to train there. Unfortunately, there isn’t very strong advocacy for swimmers in Palestine. The Palestinian Swim Federation was reorganized in 2012 and, due to some internal conflicts, they have to start to build their systems from scratch. They plan to hold competitions to record times for swimmers all over the West Bank and Gaza, to rebuild the database that is used to determine eligibility for competitions in the future. But even this simple activity has been scheduled and cancelled and rescheduled and is fraught with conflict and rumors of corruption. Moreover, although there have been many gains in the sport, Amani is still the only woman in the entire Palestinian Swim Federation.

Check back for the next part of this interview to learn about Palestinian participation in the Olympics. Meanwhile, leave your comments!

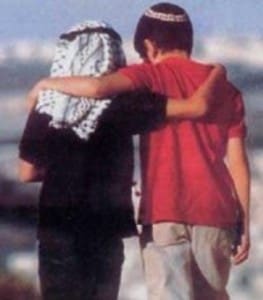

Who Are These Gorgeous Palestinians?

Normalization with Israel: Is it a Good Idea?

“Normalization” is a much-misunderstood word. Essentially, normalization refers to activities that make relationships (e.g., cultural, business, academic, etc.) between Palestinians and Israelis “normal” and not defined by conflict.

Normalization sounds like a good idea, doesn’t it? Palestinians and Israelis studying together, dancing together, playing sports together, engaging in joint business ventures — aren’t these good? If Israeli and Palestinian relationships become “normal,” won’t the Palestinian-Israeli conflict end and won’t peace reign in the Middle East?

But most of the Palestinians I know are adamantly against normalization, and while many internationals think it’s because Palestinians don’t like Israelis as people, that’s not the reason. The reason why Palestinians (and me) are against normalization is because it’s pursued as a substitute for a political settlement. Moreover, many of these efforts are shockingly naive. I’ve spoken to people who want to do joint Israeli-Palestinian acupuncture, Israeli-Palestinian meditation, and other activities that sound harmless, but scratch a bit and you’ll often find a colonial attitude underneath: “I will bring Palestinians and Israelis together and they will realize that we’re all human beings and the conflict will be ended through my intervention!”

This week, I had occasion to attempt to influence an internationally-known cultural figure who wants to initiate joint Israeli-Palestinian cultural activities. This is what I shared in my note to her:

There are essentially three related reasons not to bring Palestinians and Israelis together for cultural activities:

1-There is no “cultural” problem between Israelis and Palestinians. There is only a political problem.

Joint cultural activities distract from conflict resolution rather than contribute to it. They come from an erroneous analysis that we need to advance personal relationships between people BEFORE we resolve conflict when, in fact, we cannot advance personal relationships between people UNTIL we resolve the conflict. This is because the problem is not one of misunderstanding, but rather, structural inequality. Can you imagine bringing slave owners and slaves together to dance? No. You would have to end the structural inequality first and then folks could dance together. Now, Palestinians are not slaves, but there are currently 2.5 million Palestinians under military occupation in the West Bank, another 1.5 million under occupation and blockade in Gaza, and another 1.5 million who are colonized as second class citizens inside Israel. The rest of the 11 million Palestinians worldwide are refugees, dispossessed of their internationally enshrined rights by Israel’s unwillingness to abide by UN resolutions. This is structural inequality. I hope there will be a time when we can all dance together, but now is not that time.

2-Joint activities are over-funded and have lost credibility.

Unfortunately, there are many, many people who hold the fantasy of bringing Palestinians and Israelis together and then magically, one or the other group will say, “I’m sorry” and the conflict will be over. That’s one reason why there is so much funding for joint activities, like summer camps, theater projects, etc. Another reason is that some governments (the US included) invest in joint cultural activities precisely because they are irrelevant to conflict resolution. They don’t want all-out war, but they profit greatly from the lack of peace. The Israelis, who cannot get international development aid since they aren’t a “developing country”, run around looking for Palestinians to sign on as “partners” (usually on paper only) in order to access the funds that are set aside for joint “peacebuilding.” It’s an industry, a scam. For this reason, most of these activities have been discredited, and that makes even the genuine ones suspect.

3-There is a cultural boycott against Israel.

One of the most important Palestinian, nonviolent civil resistance activities ever is the movement for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS). It is patterned after the international boycott against apartheid in South Africa, which, along with the local grassroots movement, played a major role in isolating South Africa to the point where Apartheid was too costly and power-sharing became a viable alternative. The PACBI website now features Alice Walker’s refusal to re-publish Color Purple in Israel until the occupation is over. There is also a campaign against Circe du Soleil because they are performing in Tel Aviv in violation of the cultural boycott. Many big stars are boycotting, and many others who have performed in Israel despite the boycott have been subject to international media campaigns.

What do you think? Should internationals support the Palestinian call for an end to normalization ? Or is normalization the path to peace? Should internationals support Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions? Or does the BDS movement exacerbate the conflict?

Is anything going right in NGO-INGO relations?

This is a post I wrote for Why.Dev: committed to getting development right, a really important online community that thinks critically and constructively about development. The post is co-authored with Renee Black of PeaceGeeks, a Canadian NGO that is working with Dalia Association right now. I’ve been the main contact person with PeaceGeeks on Dalia Association’s behalf, and I initiated the post because it’s nice to share a positive experience every once in a while!

Is anything going right in NGO-INGO relations? By Nora Lester Murad and Renee Black

Nora Lester Murad, volunteer, Dalia Association:

Something is definitely wrong in NGO-INGO relations. Tension keeps popping up at global meetings and in social media exchanges. Some of it, I think, is the same power struggle as that between locals and donors (e.g., who decides how resources are used, who decides what “success” means, etc.), but there’s another aspect that’s about who “we” are as civil society, and how we manage power and privilege within “our” family. From my experience in Palestine, the disconnect is getting wider. Too often, internationals focus on projects and outputs that make sense in their organisational and funding context, but fail to take responsibility for their collective impact on local civil society – we are getting weaker and less sustainable as a result of international “aid.”

I find myself thinking about these issues all the time. I talk to colleagues around the world. I raise these issues whenever I write or speak at meetings. And the response I get is very challenging.

People say: “We understand your criticisms, but what do you suggest we do differently?”

In other words, knowing what’s wrong in NGO-INGO relations isn’t enough. We need to know how to do it better. But sadly, while I’ve had many bad and neutral experiences, I haven’t had many good ones. That’s why I’m happy to share my recent experience with PeaceGeeks, a Canadian NGO that is helping Dalia Association, a Palestinian NGO, to run an online competition.

What is PeaceGeeks doing right?

1- They called us.

PeaceGeeks contacted Dalia Association, first by email and then by Skype. As the English-speaking volunteer, I was asked to respond (we had never heard of them). Because we didn’t initiate a request for money, the dynamics lacked that sense we often feel of begging, trying to impress, of being evaluated.

2-They show respect for our leadership.

Having already read Dalia’s website, PeaceGeeks asked questions about our organisation and the context we work in. They were in learning mode; we were the experts. They also shared honestly about their organisation and their previous work. This left me feeling like there was a chance to create something together rather than being forced to take or leave a pre-packaged project on someone else’s terms.

3-They bring expertise we don’t have and at a high level.

PeaceGeeks is a collective of technical volunteers. They have expertise we don’t have. That feels very different than working with an INGO that only has money to offer.

4-They respect our timeline and limitations.

We have not been able to move as fast as PeaceGeeks. They are a huge team ready to implement ideas right away. Dalia is a small, grassroots NGO that doesn’t even have sufficient English capacity. So far, PeaceGeeks has been flexible and willing to move more slowly, making the effort to bring Arabic speakers onto their team, and understanding of our need for collective decision-making processes.

5-They are creative and responsive.

When we had difficulty coming up with the name for our philanthropy competition, they offered to incorporate a brainstorming activity into a volunteer recruitment event they were holding in Canada. Then they did extra outreach to recruit Canadian-Palestinians to participate as volunteers.

6-They act like partners.

At all steps in the process, they have shared with us what is happening on their end. For example, they explained how their board decides which projects to take on, and what kind of scrutiny we’d be subjected to. They also copy us on notes to their team so we are in the loop.

Our project—a competition to recognise Palestinian philanthropy around the world—is just starting, and there are much more work to do with PeaceGeeks around the technological interface, social media, and design. It’s a lot, and we might not be able to pull it off without help. So how do I feel so far having PeaceGeeks on our side? Hopeful.

Renee Black of PeaceGeeks:

PeaceGeeks began working with Dalia after a great chat where we could see both a clear vision of what they wanted to accomplish, and a clear role we could play a role in helping them to achieve it. Dalia is tackling a complex set of intertwined systematic issues. In the short term, they aim to challenge the perception that Palestinians are takers and not givers. The long-term objective is to engage more Palestinians in philanthropy and on questions on the effective use local resources to address local issues, towards reducing dependency on international aid and strengthening local accountability.

Breaking this unsustainable and disempowering pattern is no simple task. Dalia has chosen to begin addressing this problem through a contest that asks Palestinian youth to identify examples of Palestinian philanthropy in its various forms, whether it be sharing money, time, resources, talents and networks. They want a culture among youth who see that they have a role to play in addressing issues that affect their communities.

After meeting with Dalia, we identified three key areas where we could help make this contest possible. First, they needed a web developer to help create the website pages for the contest on their website and to train their web team in Jordan in how to replicate and manage these pages. Second, they needed a campaign name, brand and logo to help communicate the contest to stakeholders. Third, they needed help in building the capacities of their staff to make effective of use social media and blogging tools to spread the word about the contest to youth and solicit submissions. And all of this needed to happen in a very short time frame because of cutoff from one of their donors.

At first, we weren’t sure if we would be able to help because of the short turn-around time, but the project quickly piqued the interest of our volunteers, and within three days, we recruited web developer Scott Nelson, Arabic-speaking graphic designer Neeveen Bhadur and social media expert Carey Sessoms. We are now recruiting an experienced Arabic-speaking blogger to help Dalia to understand how blogging can help with their work. Along the way, we have been talking to Dalia about their evolving situation and making sure that the help that we are providing is timely and relevant.

We see our role as enablers of change. We can’t lead initiatives to address issues affecting people in other places. But what we do is help organisations like Dalia to get the tools and capacities they need to execute projects, better manage their resources or reach and engage their constituents effectively so they can solve local issues. And in the process, our volunteers get an incredible opportunity to both learn about how communities around the world are solving local problems and playing a role in helping them do it.

Check back for a follow up post in three months or so as we look back honestly about what worked and what didn’t. Meanwhile…

What are your experiences with local NGO-INGO relations?

Water Torture

Gideon Levy, one of Israel’s best journalists, just published an article in Haaretz newspaper exposing the Israeli practice of confiscating water containers from Palestinians and Bedouins in the Jordan Valley. I thank Sam Bahour of ePalestine for bringing the article to my attention. Since we’re on the topic of water, I thought it would be helpful to direct your attention to the article, which even I found quite shocking. Can human beings really deny other human beings the water they need to drink in order to live? Well, after you read the article, watch this short, excellent video on +972, produced by an Israeli NGO, about the water shortage in Al-Dik, a Palestinian village.

In fact, these types of injustices happen all the time and they are documented, in Hebrew and English, in the Israeli and international press by both Israeli and international journalists. So, Israelis can’t say they don’t know what’s going on, and neither can we.

Please click “leave comment” to the left of this post to share your views.

International Complicity with Palestinian Oppression: Gaza’s Water Problem

I write a lot about international aid to Palestine because, in my view, the international aid system and dependence on it has a lot to do with continued Palestinian oppression.

When I wrote about the recent UNICEF procurement scandal, I was mainly concerned with how donor funds end up in Israel, the entity responsible for the hardship that donor funds purport to ease. Then I read Electronic Intifada’s coverage of the same issue. The anonymous author took a different angle. S/he implied that desalination of Gaza’s water isn’t even the right approach! Although I have no expertise in water, I decided to try to understand it enough to provoke some more constructive discussion using the UNICEF story as an example — but only one of very many — of how messy aid and development are in Palestine.

First question: How did the decision get made to spend an estimated 386 million US dollars to remove salt from Gaza drinking water? UNICEF told me their decision to pursue a 10 million desalination project was in response to a study released by the Palestinian Water Authority. In other words, they say they are responding to local, Palestinian decision-making about how to deal with Gaza’s water problems.

The Palestinian Water Authority kindly shared the truly impressive document, “The Gaza Emergency Technical Assistance Programme (GETAP) on Water Supply to the Gaza Strip, Component 1 – The Comparative Study of Options for an Additional Supply of Water for the Gaza Strip (CSO-G). The Updated Final Report [Report 7 of the CSO-G], 31 July 2011.” (I can email it to you upon request.) It describes the process and outcomes of a rapid planning process in 2011 that resulted in nine interrelated water project proposals. The report describes how all the options were generated, analyzed and categorized based on criteria. A follow-up conversation with David Phillips, the report’s writer, was also enlightening.

After a lot of thought, here’s where I now stand (until convinced otherwise):

First, the report says desalination is urgently needed. But everyone seems to agree that desalination would not be “urgently needed” if it weren’t for Israel’s continuing occupation and blockade and the non-conclusion of the permanent status negotiations about water. If there were no political problem, Gaza and Israel would share water resources fairly, and Gazans wouldn’t be drinking salty, polluted water. So, the desalination option accommodates Israel’s siege — it is a bandage that does not address the root causes of the problem.

Moreover, desalinating water, while alleviating suffering of Palestinians, would also reduce pressure on Israel to comply with customary international water law and International Humanitarian Law. In fact, this is a major reason it was rejected, up till now, by Palestinians and why Israel has supported the desalination option. For these reasons, desalination is a politically costly option, and one that should only be pursued in the context of broad public input. Has there been broad public input? Not according to critics of the decision.

Second, large-scale desalination isn’t possible without guaranteed, uninterrupted energy, which doesn’t exist in Gaza (due to the Israeli siege). Therefore, the feasibility of the large-scale desalination option relies on costly, short-term “fixes” (e.g., generators) that may or may not be allowed in to Gaza by Israel. In the context of the Israeli siege on Gaza and Israel’s repeated destruction of Gazan infrastructure (including the donor-funded airport, power plant, schools, etc.), the desalination option is of questionable feasibility.

Third, there are many parties involved that have pre-existing interests in desalination and privatized approaches to water, including France, Israel and possibly Spain, making their support for desalination in Gaza a potential conflict of interest. Enhanced scrutiny to ensure integrity of all actors is critical.

Fourth, there is a dangerous pattern of inaction (or ineffective action) followed by a crisis, which is then used as an excuse for poor process. In the case of the final report that is now being used as the defining Palestinian policy document, it was an initiative of the consultant! The consultant approached Norway, and Norway funded it. The “opportunity” was offered to the Palestinian Authority. No matter how common this process is, it’s bad process and contradicts international best practices in local ownership of development. (I am completely impressed with the quality of the consultant’s work, but this doesn’t excuse the process.) Please note this: this pattern of crisis creation is built in to the “humanitarian” response system that claims to maintain credibility by staying out of politics. Humanitarian actors (who are funded, let’s be honest, by political interests, may see an impending problem, but they don’t get really involved until it’s gotten so bad that it’s a humanitarian crisis. Then, because there is a “crisis” there is justification for less local control, fast decision-making, and over-spending on “alleviation,” rather than a genuine political effort to resolve the underlying injustice.

Fifth, there is a serious distortion of the concept of “consensus.” In this case, as in all others I’ve studied, the internationals consider the Palestinian Authority as proxy for public support. But given that the PA has neither de jure nor de facto jurisdiction, and given that the PA was installed and is maintained by donors, and given that there are few if any real accountability mechanisms that people can use in relation to the PA, is the international position credible? In this case, like most others, it is hard to imagine there was very much of a local consensus process, when the final report isn’t even available in Arabic.

Sixth, I was pleased when the report identified the first screening criterion as “political” but disappointed when they elaborated it to mean: “Is this option available/feasible in the current political environment?” This is the HEART of the problem with humanitarian aid—they continue to put feasibility above rights. This makes humanitarian response complicit. If we desalinate because fair and legal sharing of resources isn’t acceptable to Israel, then we are enabling the current situation. No, not just enabling it, we are funding it! In fact, this report, like nearly all the other “technical” documents, identifies the problem as political but is not willing to focus their analysis and strategy on achieving a political solution. (But don’t we need a plan to follow when the political solutions fail, you ask? Yes, in theory, but when the political solutions fail for 64 years, then you have to ask if compromise isn’t part of the problem.)

Consider this: The report says, “The principles of customary international water law – which bind all States, whether or not they have signed specific conventions – support a case that the Gaza population should receive a much higher volume of fresh water from the resources shared with Israel. Unfortunately, however, no progress has been made in the negotiation arena on this matter, to date.” (p. 18) But does the report suggest specific ways to hold Israel accountable for its non-compliance with international customary water law? It does NOT!

And consider this circular logic that seems embedded in the report (and in the whole aid system): “We threw out the best option of fair allocation because it wasn’t feasible, so we’re instead accepting the desalination option (which was rejected in the past because it compromises our negotiating position), which relies on materials, parts and electricity that Israel may or may not allow into Gaza, which means that it too isn’t feasible.”

Where is the end to this craziness?